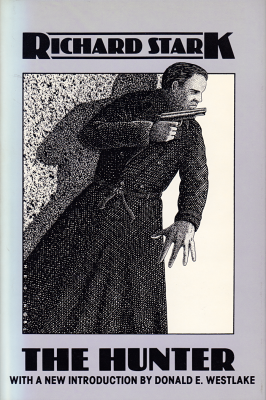

Fifth Print (Hardcover) (1981)

Generally speaking, I don’t think writers know who they are; it’s a disability–and an advantage–they share with actors. And it’s probably just as well, really. Self-knowledge can lead to self-consciousness, and in a writer self-consciousness can only lead to self-parody. Or silence.

Whereas actors receive endless surrogate identities in the roles they’re given to play, writers tend to begin their search for identity in their predecessors. Every one of us began by imitating the writers we loved to read. Those writers had made their words so real and appealing for us that we tried to move in and live there.

I was the right age at the right time to be very heavily influenced by the arrival of Gold Medal Books. These were in the fictional form known as the novel; but not really–or so it seemed at first. They were stripped down and lumpy and crude, like a beach buggy. Half the time they seemed little more than 50,000-word short stories; all that build-up, all those characters, all that preparation of setting and emotions and scenes and relationships, just to end in a shootout in a swamp. These yellow-spines paperbacks had compulsive strength, but without beauty, like acid rock; but they were interesting.

And either the books got better or my critical sense got worse. In any event, I began to make sense among the by-lines in this new garden, and to realize that here too there were gradations from very good to very very very very bad. Once I’d separated the writers from the bricklayers, everything was fine.

Gold Medal introduced me to John D. MacDonald, Vin Packer, Chester Himes, David Goodis and, by far the most important, Peter Rabe. (Rabe’s Kill the Boss Goodbye [1956] is one of the best books, with one of the worst titles, I’ve ever read.) The understatement of violence, resulting from Rabe’s modesty of character rather than modesty of experience (which is why Hammett had it down pat and Chandler could never quite make it work), was refined in these books to a laconic hipness I could only admire from afar.

(And still do. I’ve never met Rabe, and though I’d love to I’m not sure I should. What would I say to him? What would the poor man be forced to say to me?)

Rabe was not my only teacher, nor did I learn only from the tough crime novel. One of the early Gold Medals, a beautiful western by Clifton Adams called The Desperado (1950), a novel with that same compact, understated, almost reluctant treatment of violence, first introduced me to the notion of the character adapting to his forced separation from normal society. Peter Rabe, in book after book, refined that idea.

I had discovered I was a writer when I was eleven; the world took several years longer to reach the same conclusion. By 1960, however, in my mid-20s, I was at last a published writer (with Random House and some magazines), I’d quit my final honest job, and I was lunging shakily forward into my vocation. What I wanted to do was gather up armloads of words the way we used to gather up armloads of snowballs when I was a kid; every one with a small hard rock in the middle. I wanted to explain, but more than that I wanted to affect. We all know that feeling from being called on the carpet in the principal’s office; as we start on that labyrinthine lie, as we tread out over that expanse of thin ice, terrified but committed to self-preservation through prevarication, we keep dropping in the suggestive detail, the pregnant inference, the double-edged word, hoping that the accumulation of technique will somehow overpower the fact that the principal has the goods on us and we don’t have a leg to stand on. That’s when the use of words creates a nervous thrill, and it was that nervous thrill I wanted to recreate, both for me and my reader, in my choice of which words to wing at the page, each one concealing its tiny hard rock. (Later, I learned that comedy uses the same methods for even more disreputable motives, but I’m talking now about my early days.)

In 1962, I was trying to write a first-person novel in which no emotion would ever be stated; only the physical side-effects of emotion would be described, as various high-tension things would happen to and around the narrator. The book was eventually finished, and published in hardcover by Random House as “361” (1962), but halfway through its writing I’d stopped for a while, deflected by an idea for a book I thought of as a Gold Medal.

That’s what I wanted, of course, to have two publishers for my work, one for hardcover and one for soft. It seemed to me a very professional thing to have a second position to fall back to. Though I’d had a couple of books published by Random House my life as a self-supporting writer was far from assured and I already knew, unfortunately, that robbery was a tactic of last resort.

The idea of the book had come about in a very mundane way; I walked across the George Washington Bridge. I’d been visiting a friend about 30 miles upstate from New York, and had taken a bus back to the city. However, I’d chosen the wrong bus, one that terminated on the New Jersey side of the bridge instead of the New York side (where I could catch my subway). So I walked across the bridge, surprised at how windy it was out there (when barely windy at all anywhere else) and at how much the apparently solid bridge shivered and swung from the wind and the pummeling of the traffic. There was speed in the cars going by, vibration in the bridge under my feet, tension in the whole atmosphere.

Riding downtown in the subway I slowly began to evolve in my mind the character who was right for that setting, whose own speed and solidity and tension matched that of the bridge. People I knew came and went, but he quickly took on his own face, his own hard-skeletoned way of walking; I saw him as looking something like Jack Palance, and I wondered: why is he walking across the bridge? Not because he took the wrong bus. Because he’s angry. Not hot angry, cold angry. Because there are times when tools won’t serve, not hammers or cars or guns or telephones, when only the use of your own body will satisfy, the hard touch of your own hands.

So I wrote the book, about this sonofabitch called Parker, and in the course of the story I couldn’t help starting to like him, because he was so defined; I never had to brood about what he’d do next. He always knew. And the suspended experiment in unstated emotion in that first-person hardcover novel became something slightly different in this third-person paperback. To some extent, I suppose, I liked Parker for what he wouldn’t tell me about himself.

I liked him, but I killed him off. He was, after all, a villain, and he killed people, and I wanted somebody to publish the book. In 1962, Hayes office mentality was still very strong throughout the arts; bad guys didn’t get away with it. The most one could hope for was an “ironic” comeuppance. So at the end of the book Parker got shot down by the cops.

I also got shot down; Gold Medal rejected the book. That was very depressing. It hadn’t occurred to me that Gold Medal wouldn’t agree I’d written a Gold Medal book, I’d even put a Gold Medal pen-name on the script: Richard, from Richard Widmark in Kiss of Death (1947), and Stark, because I wanted a name/word that meant stripped-down, without decoration. I was all dressed up, in other words, but my natural family didn’t recognize me, so I had nowhere to go.

Fortunately, agents are not given to despair, and further submissions were made, and then an editor named Bucklyn Moon, at Pocket Books, phoned me and said, “I like Parker. Is there any way you could rewrite the book so that Parker gets away, and then give us two or three books a year about him?”

My first reaction was excitement, of course, but my second was worry, and my third was confusion. Did I want to write a series? I’d never realistically thought of doing one, never thought of myself as that kind of writer (whatever I meant by that), but the idea was very tempting once it had been broached. There was the money, certainly, and money is always a very important consideration. Money is the net, the support rope. Money is gravity. Money is the only thing that keeps us from falling into the black vacuum between the stars.

But there was also Parker; the character himself. One problem for me, in earlier consideration of doing a series, had always been that my characters persisted in using themselves up in the course of their very first story. Having solved their problems, having cleared their name and conquered their enemies and won the girl and gotten everything else they wanted (like a regular hero), having struggled that one time all the way through to “The End,” every one of them would clearly settle down to normal lives forever.

But not so Parker. He burgeoned with stories from the very beginning, and in fact it was the sixth book in the series before I had to find a plot that didn’t come directly from seeds planted in The Hunter (1962). (Maybe that’s why number six is the weakest of the lot.)

As I said, in some subterranean way Parker had come out of or been formed by that experiment in unstated emotion in “361”, and his habit of doing rather than reacting has made him for me the ideal series character; since he won’t tell me what he really wants, he can never use himself up by becoming completely satisfied.

I don’t mean to be hyperbolic when I suggest my own creation is in some ways still mysterious to me. I record his coins, and I know when what I put down is right, but I can’t always explain it, least of all to myself. Why does Parker wait in dark rooms? Why is he so totally loyal without ever showing comradeliness? What is the money for?

Going back to Buck Moon’s suggestion, I did hesitate for some time, unsure what might lay further down that road. I was very aware of the dangers inherent in sequels; any number of writers have returned to a well only to find it poisoned. (A sequel to The Desperado, that early Gold Medal Western, was written and was so bad it almost destroyed the original.) Nevertheless, finally, because of Parker, and also because of money (a motivation Parker would understand), and also because of the implicit test of my skills (another nod from Parker), I told Buck Moon I’d give it a shot.

The change in The Hunter was so easy, so easy. It became at once evident that my earlier ending had been false, that Parker wouldn’t have permitted himself such a sleazy finish. When I let him have his way with those cops, he was even quicker and less emotional than usual; because I was watching, I suppose, and life was starting. The look he gave me over his shoulder as he went through the revolving door contained no gratitude, but on the other hand it didn’t contain scorn either. He isn’t a wiseguy.

A few years after his birth, I discussed Parker with a movie director for a (finally aborted) planned film from one of the books, and this director claimed that Parker was really French, since the difference between fictional French robbers and fictional American robbers is that the French steal because that’s what they do, while the Americans steal to get money for their crippled niece’s operation. English-language villains (other than Iago) have to be explained, while French-language villains are existential.

It was an interesting distinction he’d found there, but I thought it at the time too narrow, and I still do, since in every other respect Parker is as American as Dillinger. In fact, I think he may have appeared now and again in the past, in war stories and police stories and even Westerns, the silent, moral neutral fellow barely visible in a dark corner of the setting, who suddenly and inexplicably helps the hero out of a tight spot, then laconically fades into the shadows again, with no explanation asked or given. That was romantic bunkum, of course; it would take more than a hero in trouble to make him really take a hand. But the writers were aware of him back there, and wanted to use him somehow. So did I, but without embarrassing either of us.

Donald E. Westlake

New York City