Heaven Help Us

Astrogator Pam Stokes, beautiful arid brainy and blind to passion, paused in her contemplation of her antique slide rule to check the webbing that held her to the pod. “All set.”

“What an exciting moment,” Billy said. A handsome young idealist, he was the Hopeful’s second-in-command and probably the person aboard who believed most fervently in the ship’s mission. “I wish the captain were up here.”

Captain Gregory Standforth himself wandered onto the command deck at that moment, holding a stuffed bird mounted on a black-plastic-onyx pedestal. “Isn’t she a beauty?” he asked and held up this unlovely creature that in death, as in life, was blessed with a big belly, a pink tuft on top of its orange head and a lot of bright scarlet feathers on its behind. The captain had bagged it on their last planet fall, Niobe IV, a.k,a. Casino. “I just finished stuffing her,” he explained. Taxidermy was all he cared for in this life, and only the long, glorious traditions of the Standforth family had forced him into the Galactic Patrol. Conversely, only those traditions had forced the patrol to accept him.

“Heaven ahead, sir,” Billy said. “Secure yourself.”

The captain studied his trousers for open zippers. “Secure myself?”

“Take a pod, Captain, sir,” Billy explained. “Landing procedure.”

“Ah.” Settling himself into a pod, the captain slid his bird onto a handy flat surface, thereby inadvertently pushing a lever. A red light flashed on all the control consoles, and there came a sudden, brief whoosh. “Oh, dear,” the captain said. “Did I do something?”

Billy studied his console. “Well, Captain,” he said, “I’m sorry, sir, but you just ejected the laundry,”

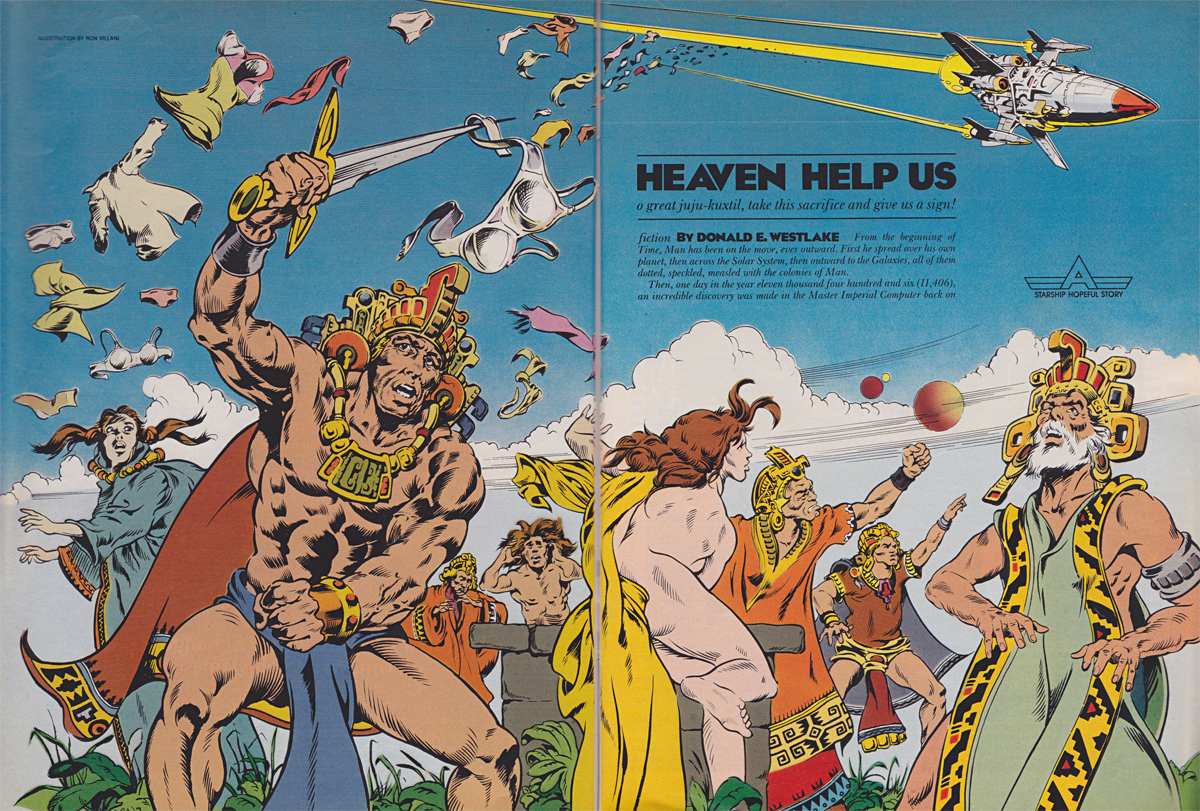

“O great Juju-Kuxtil. Oh, take, we beseech you, this sacrifice of our youngest, our purest, our finest daughter. Find this sacrifice worthy of your mighty eyes and defend us from the yellow rain. If this sacrifice be good in your eyes, give us a sign.”

Achum bowed his head in unbroken silence. He prayed, “If she should be spared, who is my own daughter Malya of only sixteen summers, O great Juju-Kuxtil, give us a sign.”

The Hopeful’s laundry fell on everybody.

Pandemonium. Achum and Malya and the congregation all struggled and fought their way out from under the laundry. “Achum!” the worshipers cried. “Achum, what’s happening?”

“A sign!” Achum shouted, spitting out socks. “A sign!”

A worshiper with a greasy work glove rakishly atilt across his forehead cried, “Achum! What does it mean?”

“I’m not sure exactly what it means,” Achum answered, looking around at this imitation of a rummage sale, “but it sure is a sign.”

A worshiper pointed upward. “Achum, look! From the sky! Something huge is coming!”

Councilman Morton Luthguster, stout and pompous, representative of the Galactic Council on this journey of discovery and reunion, sat in his stateroom in prelanding conference with Ensign Kybee Benson, social engineer, the saturnine, impatient man whose job it was to study the lost colonies as they were found and prepare reports on what they had become in the half millennium of their isolation.

“Well, Councilman,” Ensign Benson said, “they were a religious people five hundred years ago. The colony here was founded by the Sanctarians, a peaceful, pious community determined to get away from the strife of the modern world. Well, I mean, what was then the modern world. They named their colony Heaven.”

“Charming name,” Luthguster said, nodding slowly, creating and destroying any number of chins. “And, from what you say, a simple, charming people. I look forward to their acquaintance.”

“Landing procedure complete,” said the loud-speaker system in Billy Shelby’s animated voice.

“Ah, good,” Luthguster said, heaving himself to his feet. “Come along, Ensign Benson. I wonder if I recall the Lord’s Prayer.”

The Hopeful’s automatic pilot had set the ship gently down on a wide, barren, rocky plain, similar in appearance to several unpopulated islands of the coast of Norway. A door in the side of the ship opened, a ladder protruded itself slowly from within, like a worm from an apple, and once it had pinged solidly onto the stony scree, Councilman Luthguster emerged and paused at the platform at the ladder’s top. Captain Standforth, Billy Shelby and Ensign Benson followed, and all four stared down at the welcoming committee below.

Who were Achum, his unsacrificed daughter Malya and all the worshipers, every last one of them decked out in the Hopeful’s laundry. And when Achum looked up at that fat figure atop the ladder and recalled the god statue in his church, hope became certainty: Prostrating himself, with his forehead on the ground, he cried out, in a voice of terror and awe, “Juju-Kuxtil! Juju-Kuxtil!”

The other worshipers, quick on the uptake, also prostrated themselves, and the cry went up from one and all: “Juju-Kuxtil! Juju-Kuxtil!”

“Not very much like my religion,” Luthguster said and led the group down the ladder to the ground, where the worshipers continued to lie on their faces and shout out the same name. The instant Luthguster’s foot touched rock, Achum scrabbled forward on knees and elbows to embrace the councilman’s ankles. “Here! Here!” cried Luthguster, not at all pleased.

Achum half rose. “Hear, hear!” he shouted. “Hip, hip —”

“Hooray!” yelled the worshipers.

“Hip, hip —”

“Hooray!”

“Hip, hip —”

“Hooray!”

Ensign Benson had approached one of the prostrate worshipers, and now he attracted the fellow’s attention with a prodding boot in the ribs. “Say, you. What’s going on around here?”

“Juju-Kuxtil!” answered the wide-eyed worshiper and nodded in awe at Luthguster. “God! It’s God!”

Achum was on his feet, prancing around, crying, “A feast for Juju-Kuxtil! A feast! A feast!”

Luthguster, beginning to get the idea, looked around and visibly became more enamored of it. Frowning at him, Ensign, Benson said, “That’s God?”

“He’s shorter in person, isn’t he” said the worshiper.

Sotto voce, while the speech went on, Councilman Luthguster asked Ensign Benson, beside him at his other hand, “What’s happening here?”

“Apparently,” Ensign Benson murmured, “some physical disaster struck this colony quite some time ago and drove these people from an advanced society, with modern religion, back to primitive paganism.”

“But what should we do?”

“Go along with them, at least for a while. Until we learn more.”

“But what’s this yellow rain he’s going on and on about?”

“We can’t ask questions,” Ensign Benson said. “We’ll find out later.”

Achum was finishing his speech: “Soon the great Juju-Kuxtil shall begin his mighty work; but first, we shall feast. A feast of welcome to Juju-Kuxtil and his angels!”

Cheers rose from the assembled natives. Achum took his seat, and platters of food — lumpy, anonymous brown stuff that smelled rather like mildew — were distributed. Hospitably, Achum said to Luthguster, “I hope you like dilbump.”

Luthguster blinked at his plate. “It looks quite, um, filling.”

Billy Shelby had seated himself next to the prettiest girl at the feast, who happened to be Achum’s daughter Malya. Smiling at her, he said, “Hi. My name’s Billy.”

“Malya.”

“What’s the matter? You aren’t eating.”

“I wasn’t planning on dinner today,” Malya explained, “so I had a big lunch.”

“No dinner? Why not?”

“I was about to be sacrificed when you all got here.”

Billy stared. “Sacrificed! Why?”

Wondering but not quite suspicious, Malya said, “For Juju-Kuxtil, of course. Don’t you know that?”

“Oh! Um. Well, I’m glad it worked out this way, and now you don’t have to be sacrificed, after all.”

She pouted prettily. “Don’t you want me to live forever with you on the Great Cloud?”

Sincerely, he said, ‘I’d like you anywhere.”

She gave him a sidelong look. “You don’t seem very much like an angel.”

“I can be surprisingly human,” he told her.

The fourth voyager on the Hopeful also at the feast was Chief Engineer Hester Hanshaw, a 40ish, blunt-featured, blunt-talking person who was much happier with her engines than at any social occasion, including religious feasts. She kept her eyes firmly down and did little more than poke at her soup and her dilbump until the native on her left said, “Excuse me.”

Hester looked at him. He was middle-aged, with a keen look about the eyes and the gnarled hands of a worker. “Yeah?”

“I was looking at that cloud you all fly around in.”

“I hope you didn’t mess it up,” Hester said.

“It’s hard to the touch. I thought clouds were soft and fluffy.”

“It isn’t a cloud,” said Hester, who didn’t believe in going along with other people’s misconceptions. “It’s a ship.”

“Make a nice lamp.”

Hester stared. “What?”

“I’m a carpenter,” the native said. “Name of Keech.”

“I’m Hester Hanshaw. Ship’s engineer.”

“What’s that?”

“I keep the engines running.”

Keech looked impressed. “All the time?”

“I mean I fix them,” Hester told him, “if something goes wrong.”

Looking skyward, Keech said, “All those clouds have engines? Fancy that.”

Covering her exasperation by a change of subject, Hester said, “What kind of carpentry do you do?”

“Oh, the usual. Sacrificial altars, caskets, suspended cages to put sinners in.”

“Cheerful line of work.”

“Tough to build things that last,” Keech commented, “with the yellow rain all the time. But we won’t have that anymore, will we, now that Juju-Kuxtil is here?”

“You mean Councilman Luthguster?”

“The million names of God,” Keech said solemnly. “Which one is that?”

“Number eighty-seven,” Hester said. “What’s in this soup? No, don’t tell me.”

On Achum’s other side sat Captain Standforth, brooding at his soup, and on his other side sat Astrogator Pam Stokes, brooding at her slide rule. “Fascinating,” she mumbled. “That asteroid belt.”

“Pam?” The captain welcomed any distraction from that soup; things seemed to be moving in it. “Did you say something?”

“This system contains an asteroid belt,” Pam told him, “much like the one in our own Solar System.”

“Oh, the asteroid belt,” the captain said, his mind filling with unhappy reminiscence. “I always have a terrible time navigating around that. You barely take off from Earth, you’re just past Mars, and there it is. Millions of rocks, boulders, bits of broken-off planet all over the place. What a mess!”

“Well, the asteroid belt in this system,” Pam said, “has an orbit that’s much more erratic. In fact. . . .” Swiftly, she manipulated her slide rule. “Hmm. It seems to me. . . .” She gazed skyward, frowning.

So did the captain, though without any idea what he was supposed to be looking at. He blinked, and a yellow stone dropped into his soup, splashing oily liquid in various directions.

“Of course!” said Pam, pleased with her calculations.

A stone bounced off the table near Councilman Luthguster’s right hand. A stone thunked into a platter of dilbump and slowly sank. A paradiddle of stones rattled in the center of the circle of feasters.

“The yellow rain!” cried Achum in sheerest horror.

Screams. Terror. The natives fled into handy burrows while the people from the Hopeful stared at one another in wild surmise. More stones fell. Achum dropped to his knees beside Councilman Luthguster, hands clasped together: “Juju-Kuxtil, save us! Save us!”

“It’s a meteor shower!” Ensign Benson cried.

“No,” Pam said, utterly calm, “it’s the asteroid belt. You see, its eccentric orbit must from time to time cross this —”

Clambering clumsily to his feet, Luthguster shouted, “Asteroids? We’ll all be killed!”

Taken aback, Achum settled on his haunches and gaped at the councilman. “Juju-Kuxtil?” Meantime, more stones fell.

Bewildered, the captain said, “Pam? Shouldn’t we take cover?”

“According to my calculations,” Pam answered, “this time we’re merely tangential with —”

A good-sized boulder smacked into the earth at Luthguster’s feet. In utter panic, spreading his arms to keep from losing his balance, he shrieked, “Stop!”

Still calmly explaining, Pam said, “it should be over almost at once. In fact, right now.”

She was right; no more rocks fell. Slowly, the natives crept back out of their burrows, peeking skyward. Achum, faith restored, bellowed, “Juju-Kuxtil did it! He did it!”

“Juju-Kuxtil! Juju-Kuxtil!” the natives all agreed. Then they joined hands and danced in a great circle around Luthguster, singing, “For he’s a jolly good savior; for he’s a jolly good savior.”

“They think I’m God,” Luthguster said complacently.

“Heaven has become debased, degenerate.”

I beg your pardon,” Luthguster said.

Captain Standforth cleared his throat. “Uh, Billy says they have human sacrifice.”

Luthguster assumed his most statesmanlike look. “I don’t believe we should be too harsh in our judgments, Captain. These people aren’t all bad. We shouldn’t condemn a whole society out of hand.”

“Of course not,” Ensign Benson said. “First, we have to understand why a society behaves a certain way. Then we condemn it.”

“According to the old records,” the captain said, “they were perfectly nice people when they left Earth — cleaned up after their farewell picnic and everything.”

“But no small settlement,” Ensign Benson said, “could survive a constant, unpredictable barrage of rocks from the sky. Everything they ever built was knocked down. Every machine they brought with them was destroyed. Every crop they planted was pounded flat. No wonder they returned to barbarism. You have to be hit on the head with a lot of rocks to think the councilman here is God.”

Luthguster puffed himself up like a frog preparatory to an answering statement; but before he could make it, Hester came in with Keech. Each carried an armload of yellow rocks. “Captain,” Hester said, “request permission to show a visitor around the ship.”

“Nice cloud you got here,” Keech said.

“His name’s Keech,” Hester explained. “He’s a carpenter; seems a little brighter than most. Thought I’d try to explain engines to him.”

“Certainly, Hester,” the captain said. He never denied anybody anything. “What are you doing with all those rocks?”

“Going to analyze them,” Hester said.

“Very good idea,” the captain said. He didn’t know what analyze meant.

Hester and Keech left, and Ensign Benson turned to Pam, saying, “Do these rockfalls happen often?”

“Very.”

“Every day?”

Pam shook her head. “Not necessarily. According to my calculations, the planet’s orbit intersects the asteroid’s orbit so frequently, in such a complex pattern, that to most people, it would seem utterly erratic.”

“Could you work out the pattern?”

“Of course. As a matter of fact, there should be another brief shower later today.”

“Then I’m glad,” Luthguster said, we’re all in the ship.”

“Billy isn’t,” the captain said. “He asked permission to go for a walk with the human sacrifice.”

“Bad,” Ensign Benson said. “When the rocks fall, the natives will lose faith in the councilman. They’ll want revenge.”

“Pretty clever,” Keech admitted. “Given the right education and equipment, a human being could do ” the same stuff you angels do.”

“You’re beginning to catch on.”

Bang, said the ship. Keech look startled, Hester annoyed. Bong, bong, bong, bongbongbong. “Yellow rain!” Keech cried.

“I wish it would lay off,” Hester muttered.

“Do you realize,” Keech demanded, what all this is doing to my faith?”

“I’m really not,” Billy confessed. “What I really am is a human being.”

“A human being?”

“Just like you. Well, not exactly like you. You’re a girl and I’m a boy.”

“I was beginning to suspect that,” Malya said. “But why does Juju-Kuxtil travel around with humans?”

“Well,” said Billy. “About Juju-Kuxtil …. ”

In rapture, she said, “He saved us from the yellow rain.”

“Ahhhh, yes and no,” Billy said, scuffing his foot in the rocks.

She frowned at him. “What do you mean?”

“Can you keep a secret?”

“Of course,” she lied.

Nerving himself up to blurt out the real story, Billy said, “Well the truth is —”

Bong; a good-sized rock landed on his head. He fell over, unconscious. Rocks suddenly started bouncing all over the place. Flinging herself onto Billy to protect him, Malya cried, “I think I know what you were trying to tell me, Billy!”

In the roofless temple, Achum led a community discussion, “Now that Juju-Kuxtil has come and stopped the yellow rain,” he said, “Heaven is ours. We can build, travel, everything.” He gestured with broadly spread hands, smiling. The worshipers smiled back. A small yellow rock landed on Achum’s right palm.

Five minutes later, when the rockfall had ended, Achum and the worshipers came crawling back out of their burrows and none of them were happy. ‘Juju-Kuxtil lied!” several shouted.

“Yes!” Achum thundered.

“Achum is a false priest!” one shouted.

“Wait a minute,” Achum said. “Hold on there.”

“You’re a false priest.”

“Now, hold on. In the first place, I’m not a false priest, and I’ll knock you down if you say that again. And in the second place, that’s a false god!”

“A false god?”

“That isn’t Juju-Kuxtil,” Achum explained. “It’s a demon trying to lead us astray. A demon disguised as Juju-Kuxtil!”

“A demon disguised as a god,” mused a worshiper. “Hmm. That makes sense.”

Ensign Benson said, “What’s funny?”

The captain entered, looking ruffled, saying, “Gee, are they sore.”

“Pam? What’s funny?”

“There shouldn’t be another asteroid fall,” she said, “for two days.”

“That isn’t asteroids,” the captain told her. “They’re throwing rocks at the ship.”

“Rocks at the ship!” Luthguster was incensed. “That’s Galactic property!”

“Actually, it’s mine,” Ensign Benson said.

“They were hollering, ‘Demon! Demon!'” the captain explained. “They think you’re a false Juju-Kuxtil.”

Luthguster gaped. “Me?”

“Councilman,” Ensign Benson said, “you’ve set back superstition on this planet four hundred years.”

Hester and Keech entered, Hester saying, “Captain, I —.”

Luthguster ran around behind a pod, crying, “Look out! There’s one of them!”

“What?” Hester shook her head. “Oh, Keech is all right. I told him the whole story,”

“I’m the soul of discretion,” Keech said.

Hester turned to the captain. “Which do you want first, the good news or the bad?”

“Hester, I hate making decisions.”

“Start with the bad,” Ensign Benson said. “Then we’ll have the good for dessert.”

“Fine. The bad news is, the rocks damaged our lateral rockets. ‘We can’t navigate.”

“Oh, my goodness,” said the captain.

Can it be fixed?”

‘I’ll have to go outside on a ladder.”

“Wear a hat,” Ensign Benson advised. “The weather’s getting worse out there..”

Pam, looking at a view screen, said, “What’s this?”

So they all looked and saw several natives approaching, pulling a wooden-wheeled cart filled with cloth.

“They’re bringing back our laundry,” the captain said.

Ensign Benson said, “I don’t think they cleaned it.”

“I’ll go get it,” Pam said.

Ensign Benson, whose dream that someday Pam would discover she was a human female had not yet died, said, “I’ll go with you.

They left, and the captain said, “Hester? You had good news?”

“I would be more than happy,” Luthguster said, “to hear good news.”

“I did a mineral analysis on those rocks,” said Hester. “The reason they’re yellow, every one of them is at least part gold.”

The natives had dumped the laundry at the foot of the ladder and had gone away with the cart, expressing their contempt. Pam and Ensign Benson cautiously descended, and when they reached the bottom, a hand reached out of the laundry and grabbed Pam’s ankle. “Eek!” she said, naturally.

Malya’s lovely face appeared among the shirts and the shorts. “Shh! It’s me, Malya; I’m on your side! Sneak me in before anybody sees!”

“My laundry never came back with a girl in it before,” Ensign Benson said.

Out of a cave onto the blasted plain staggered Billy, rubbing his head. “Ooh, that hurts,” he mumbled. “What kind of Heaven is this?” Raising his face and his voice, he cried, “Malya! Malya?”

A dozen natives leaped on him from all sides, pummeled him and, carried him away.

“So I have him hidden,” Malya said. She was on the command deck with the five Earthpeople and Keech.

“We’ll have to move the ship at once,” Luthguster said, “to his hiding place. This young lady can direct us.”

“We can’t navigate,” Hester reminded him “till I fix the lateral rockets.”

“We have a saying here,” Keech commented. “Into each life a little rock must fall.”

The captain said, “It was a mistake to pretend to be gods.”

“I agree, Captain,” Ensign Benson said. “My error. It seemed like a good idea at the time. But as long as we’ve made the mistake, we’ll have to live with it. Councilman, you’ll have to go out there and reconvince them that you’re Juju-Kuxtil.

“Me? They’ll stone me!”

“The hand that cradles the rock rules this world,” Hester said.

“That isn’t nice,” Pam said. “People shouldn’t throw stones.”

“Why not?” Keech asked, “We don’t live in glass houses.”

The captain said, “if we tell them about the gold, won’t —”

Ensign Benson said, “The what?”

Hester explained, “The yellow rain is mainly gold. If this colony went into the export business, it could become rich.”

Keech said, “What’s gold?”

“I know you’re primitive,” Luthguster told him, “but that’s ridiculous.”

“I may be primitive,” Keech answered, “but it’s you wiseacres that’re in trouble.”

Ensign Benson said, “Pam, the rockfall pattern repeats, doesn’t it? You could do a yearly calendar with the rockfalls.”

“It’s a very complex pattern, but yes, of course.”

“Could you do it in an hour?”

“Oh, my goodness,” Pam said. “I’ll try.”

The captain said, “You have a plan to help Billy, Ensign Benson?”

“If Malya and Keech will help,”

“I’ll help,” Malya said. “I don’t want anybody to hurt Billy.”

Keech said, “Is gold something that makes you rich?”

Grinning, Hester said, “I told you he was smart.”

This time, in the roofless temple, it was Billy who was about to be sacrificed. He was tied and gagged and lying on the altar, with Achum holding the stone knife over him and the worshipers eagerly watching below. Achum prayed, “Great Juju-Kuxtil, we’re sorry we were misled. Please accept this demon as a token of our esteem.” He poised with the knife.

Keech came running in, crying, “Wait! I have come from Juju-Kuxtil’s cloud! I have much to tell you!”

“After the services,” Achum told him. “First the sacrifice, then the collection, then you can talk.”

“No, I have to talk now,” Keech insisted. “That is the real Juju-Kuxtil.”

Achum shook his head and waggled the stone knife. “Stuff and nonsense. There was more yellow rain after he supposedly made it stop.”

“He was testing our faith,” Keech said.

A worshiper mused, “A god pretending to be a demon disguised as a god to test our faith. Hmm. That makes sense.”

Achum wasn’t convinced. “How can you know that, Keech?”

“They took me to their ship. I mean the cloud. Also your daughter Malya; they took her there, too.”

“Malya?” Achum looked around, called, “Malya!”

“She’s still in the cloud,” Keech said. “And Juju-Kuxtil is going to come out and talk to us.”

Achum lowered. “Oh, he is, is he?”

“He sent me to get everybody to come hear his speech.”

“Oh, we’ll come,” Achum said. “Gather rocks, everybody! This time we’ll pelt him good! And bring along the sacrifice; we’ll finish the services later.”

In a corridor of the Hopeful, by an exit hatch, the captain, Pam and Ensign Benson prepared Councilman Luthguster for his public. “Now, do remember to turn on your microphone,” the captain said, yet again. “Your words will be transmitted through the ship’s loud-speaker.”

“Yes, yes,” said the extremely nervous Luthguster.

Handing the councilman a sheaf of papers, Pam said, “Just remember, it’s an eight-month cycle, and this planet has a sixteen-month year, so the cycle runs twice a year.”

“Young lady,” Luthguster said, clutching the papers, “I have no idea what you think you’re saying.”

“Now, Councilman,” Ensign Benson said, “there’s nothing to worry about.”

“There’s nothing for you to worry about. You’ll be in the ship.”

“You’ll be behind this shield.” Ensign Benson rapped the clear-plastic shield with his knuckles. “Just give them one of the speeches you’re famous for, and they’ll calm right down. They’ll sleep for a week,”

“I do have some small reputation as a peacemaker,” Luthguster acknowledged, though he continued to blink a lot. “Very well. For the future of mankind on this planet.” And he stepped onto the small platform that would swing out onto the side of the ship once the hatch was opened.

“Knock ’em dead,” Ensign Benson advised him and pushed the button.

A frozen smile of panic on his face, Luthguster permitted himself to be swung slowly out into plain sight high on the side of the gleaming, cigar-shaped Hopeful. And below, bearing armloads of rocks and carrying the trussed-up Billy on a long pole, came the natives. They did not look particularly reasonable.

“People of Heaven,” Luthguster said, but, of course, he had forgotten to turn on his microphone, so nobody heard him. Flicking the thing on, he tried again:

“People of Heaven,”

“There he is! There he is!”

“Let he who is without sin cast the first stone.”

A thousand stones hit the plastic shield. Luthguster ducked, then recovered, crying out, “Surely, some of you have sinned!”

“The stones bounce off him!” Keech shouted. “You see? It is Juju-Kuxtil!”

Achum, poised to throw another stone, hesitated, becoming uncertain. “Could I have been wrong?”

The other worshipers had already prostrated themselves, noses in the pebbles, and were wailing, “Juju-Kuxtil! Juju-Kuxtil!”

Privately to Achum, Keech said, “Would you rather be safe or sorry?”

“Juju-Kuxtil!” Achum decided and prostrated himself with the rest.

Quickly, Keech released Billy, while Luthguster delivered his speech:

“People of Heaven, I have tested you, and your faith is not strong. But I am merciful, and I will not return my golden rain to you for” — he consulted Pam’s papers — “two days. At ten-fifteen next Tuesday morning, watch out!”

“There you go, kid,” Keech said to the freed Billy. “Get to the ship before the councilman louses up.”

Billy scampered to the Hopeful while Luthguster rolled on:

“I will never be more than a stone’s throw from you all. Achum shall remain my representative here on Heaven, but I won’t need any more human sacrifices.”

“Drat,” the worshipers muttered. “No fun anymore.”

“Also, the man who is known among you as Keech will henceforth carry this list, which will tell you the times of all the golden rains that will ever be, from this day forward. You will be smart enough to get in out of the rain, but after every rain, there will be a time to gather stones together. The streets of Heaven are paved with good investments, and I will want them returned. Heaven knows what I’m talking about. Upon these rocks we shall build a mighty nation. Right on this spot here, I want these rocks of ages left for me. Keech will be in charge of all that. I will send ships from Earth to Heaven, and they will trade you machinery, medical supplies, technical advisors and everything else you need, in exchange for my rolling stones. Earth helps those who help themselves. Together, we shall make an Earth right here on Heaven. And remember, a vote for Juju-Kuxtil is a vote for peace, progress and sound financial practice.”

Keech led the worshipers in a resounding cheer as Luthguster was wheeled, waving and smiling, back into the ship, where, once the hatch was shut, Ensign Benson said, “Councilman, that may have been your finest hour.”

Luthguster was dazzled. “By Heaven,” he said, “what a constituency!”

“So do I,” Malya admitted. “Earth must be a wonderful place after Heaven.”

“Any place is Earth,” Billy told her, “with you there.”

They were deep in embrace when Ensign Benson appeared at the head of the ladder, calling, “Come on, Billy, or we’ll take off without you.”

“They can’t take off without me,” Billy confided to Malya. “I fly it.”

“But you must go. Goodbye, Billy.”

“Goodbye, Malya.”

Malya walked to a nearby rubble heap, where she and Keech watched the Hopeful prepare for take-off. “Gee, what a swell bunch,” Malya said.

“That Hester,” Keech said, “was the most sensible woman I ever met.”

“I wouldn’t call Billy exactly sensible,” Malya said, “but he was swell.”

“Lift-off,” Billy said. All six Earthpeople were present on the command deck.

“Captain,” Pam said, studying her console, “the ship is overweight.”

Diplomatically careful but with an edge of sarcasm, Ensign Benson said, “I believe the councilman smuggled gold aboard.”

“Smuggled?” Luthguster was all pompous bluster. “Merely a few souvenirs.”

“I’m sorry, Councilman Luthguster,” the captain said, “but you’ll have to eject them.”

“Humph,” said Luthguster.

“I’m still not sure about that crowd,” Achum told her. “No more human sacrifices. Would the real Juju-Kuxtil talk like that?”

Luthguster’s souvenirs crashed to the altar beside him. Achum froze, then his eyes swiveled to look at the fresh rocks on the altar. Still moving nothing but his eyes, he looked up at the statue. “Ahem,” he said. “I guess maybe he would.”

“Come along, Father,” Malya said. “Dilbump for lunch.”