Hitch Your Spaceship to a Star

BREAKFAST ON THE HOPEFUL consisted of ocher juice, parabacon, toastettes, mock omelet, papjacks, sausage, (don’t ask) and Hester’s coffee. It was called Hester’s coffee because Hester made it and Hester drank it; the others had to draw the line somewhere.

This morning, all hands had gathered for the prelanding meal. At the head of the round table sat Captain Standforth himself, under the glassy eyes of nearly two score defunct birds mounted on the walls, the stuffing of which was his only true vocation. Descended from those Standforths, the ones who had so routinely over the pass seven generations covered themselves with glory in the service of the Galactic Patrol, the captain had been compelled by both his family and destiny to enlist when his turn came, just as the patrol had been compelled by family and history to take him, inadvertently and unhappily proving that sometimes neither nature nor nurture may create character. Taxidermy? A Standforth? Regrettably, yes.

Gathered around, scoffing down the fabrifood, were the rest of the expendable captain’s expendable crew, plus his lone expendable passenger, Councilman Morton Luthguster, as plump and pompous as a pouter pigeon crossed with a blimp. The crew consisted of second-in-command Lieutenant Billy Shelby, young and idealistic but not to awfully bright; Astrogator Pam Stokes, very bright and very beautiful but a stranger to passion; Ensign Kybee Benson, whose encyclopedic knowledge of human societies did not keep him from being personally antisocial; and stockily blunt Chief Engineer Hester (of the coffee) Hanshaw, proud mistress of the engine room.

The captain wiped his lips on a toastette, then ate it. “Well,” he said to his murky band, “we’ll be landing soon.” His mild eyes gleamed with visions of this unknown planet and the unimaginable new birds he would soon disembowel.

Councilman Luthguster, swirling a forkful of papjack in pseudoleo, said, “What is this place we’re coming to, Ensign Benson? What are its characteristics?”

“No one knows for sure about this one, Councilman,” the ensign told him. “The old records simply say the colonies were a group of like-minded people whose goal was a simple life free of surprises.”

“Well, we’ll be a surprise,” the councilman said.

![]()

Councilman Luthguster said, “What’s the name of the place, Ensign Benson? I’ve noticed that the name the colonists give their settlements frequently offers a clue to their social structure.”

“It’s called Figulus,” Ensign Benson said.

“Figulus?”

Blank looks around the table. Billy Shelby said, “Wasn’t he one of the founders of ancient Rome? Figulus and Venus.”

“No, Billy,” said Ensign Benson.

![]()

Jim frowned skyward. “You don’t suppose they got the coordinates wrong? Landed someplace else on Figgy?” Behind them, on the knoll where they stood, the pleasant town dreamily awaited.

“They’re dawdling over their breakfast, like as not,” Hank replied. “In fact, there they come yonder.”

![]()

“Publius Nigidius Figulus,” Ensign Benson said. “He was the most learned Roman of his age, a writer and a statesman, died circa forty-five BC”

Billy looked sad. “Died at the circus? That’s awful.”

“Terrible,” the ensign agreed. “Figulus was most noted for his books on religion and—–”

“We’re,” Pam Stokes said, her ancestral slide rule moving like a live thing in her slender-fingered hands, a subtle alteration simultaneously taking place in the faint aura of engine hum all about them, “here.”

Everyone jumped up to look out the view ports at Figulus, third of ten planets in orbit around the Sollike star called Ptolemy. Only Ensign Benson remained at the table, draining his vial of ocher juice. “And astrology,” he finished.

![]()

“People of Fugulis—–”

“Hi, Senator,” Jim said.

Councilman Luthguster frowned across the top of his P.A.-system microphone at the two locals at the foot of the extruded stairs. He was on the platform at the top. Both were middle-aged, mild-mannered, Jim with a gray cardigan and a pipe, Hank with eyeglasses and a tweed jacket. All four elbows sported leather patches. “I am a councilman,” he informed them.

“Ha!” said Hank. “That’s a five-buck you owe me, Jim.”

Jim scratched his head. “I would have sworn a plenipotentiary from Earth would be at least a senator.”

Councilman Luthguster stared. “Í haven’t told you that yet,” he told the world through the P.A.-system.

Just inside the ship where the others waited, Ensign Benson frowned and said, “What’s going on out there?” He edged closer to the open hatch, where he could hear both sides of the conversation. ”Well, in any event,” Hank was saying, while his pal Jim sadly produced a five-buck from his wallet and handed it over, “the councilman is not the one we have to talk to here. No, we want the man in charge.”

“You mean the captain?”

Hank said, “No, no, he’s just some sort of hobbyist along for the ride. We want the—what will you call him? Social scientist. Anthropologist.”

“Sociologist,” Jim suggested. “Ethnologist.”

Ensign Benson stepped out onto the light. “Social engineer,” he said.

“How do you do, sir,” Hank said, smiling behind his glasses, coming up the ladder with hand outstretched. “I’m Hank Carpenter, mayor of Centerville.”

Back on the ground, Jim made a dang-it gesture with his pipe. “I knew he’d be a Scorpio! Dang it, that’s what we should have bet on.”

Ensign Benson accepted Hanks firm but friendly handshake. “Centerville?”

“Well, sir,” Hank said, “it happens that this is the center of the universe. May not look like much, but that’s what it is and why our forebears came here. But lets quit jawing. You and the councilman and the four inside the ship, come on to town and meet the folks.”

Ensign Benson held tight to the stair rail. “Four inside?”

“Well, there’s your captain,” Hank said. “Tall, skinny, distracted fella. A Pisces. And his number two, a nice young boy but not too quick upstairs—probably a Moon Child. Moony, anyway.”

“Show-off,” Jim said. He was still smarting over his fiver.

Hank went on, pretending not to notice. “Then there’s your navigator—“

“Astrogator.”

“Same thing, just gussied up. A highly motivated young person, probably female.”

“Not yet,” Ensign Benson muttered.

“But definitely Virgo.”

“That I’ll go along with.”

“Now, your engineer,” Hank went on, “a solid Taurus, but we just can’t decide if it’s a man or a woman.

“Nobody can,” Ensign Benson said.

“I heard that,” Hester said, coming out onto the platform to shake a wrench at the ensign. “I’m a woman, and don’t you forget it.”

“Why not?”

“Come on, folks,” Hank said, gesturing toward town. “You’ve had a long, hard journey; come along and relax.”

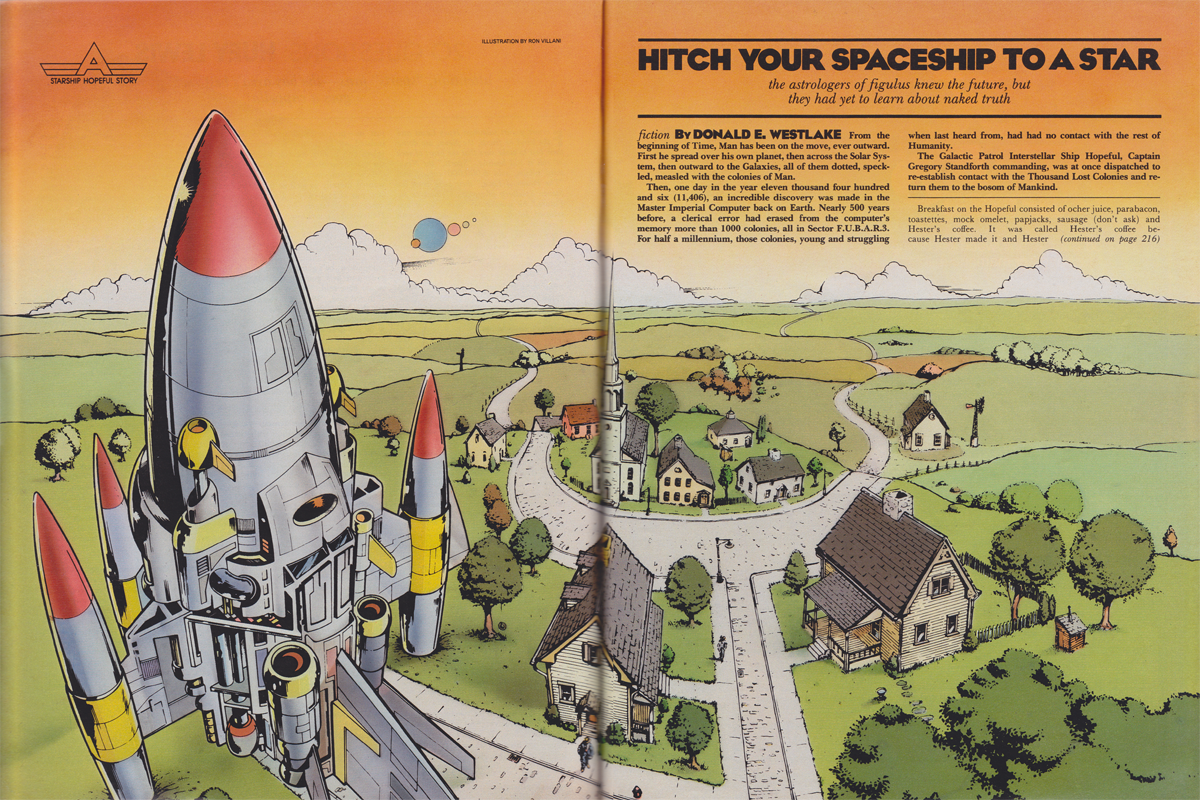

The captain, the lieutenant and the astrogator joined the three other earthlings on the platform and they all looked off toward town. A pretty little place with peaked roofs, a traditional white steeple and a sports ground alive with running, yelling children, it nestled in a setting of low hills where neat farms mingled with elm groves, the whole area very much like bits of Devon and Kent—the parts beyond commuting distance from London. “What a nice place,” Pam said, her slide rule for one instant forgotten.

“You’ll learn to love it,” Hank assured them, “in time.”

![]()

“Chick, chick, Nero,” Jim said as Hank explained to the Earthers, “Our energy sources are really very slender. No oil, no coal. Hydropower and solar power give us enough electricity to run our homes and businesses, but there was no way we could keep powered transportation. Fortunately, there were several indigenous animals capable of domestication, including the like of old Nero here.”

Nero, a gray-and-white creature that might very well pass for a horsy steed in the dusk with the light behind it was apparently quite strong; without effort it pulled this ten-seater surrey and its eight passengers along the gently up-and-down crushed-stone road toward the town. A farmer in a nearby field, plowing behind another Nero, waved; Hank and Jim and Billy and Hester waved back.

“Have any birds here?” the captain asked.

“Oh, all sorts.”

Ensign Benson had been deeply frowning, intensely brooding, acutely staring into the middle distance, but now all at once he nodded and said, “Hyperradio.”

Jim frowned around his pipe. “Say what?”

“You must be in hyperradio contact with one of the colonies we already visited.”

“Not us,” Jim said. “never heard of hyperradio.”

“Then someone else has been here from off planet. Recently.”

“No, sir.” Jim shook his head and Nero’s reins.

Hank said, “You’re our first visitors in five hundred years. You’ll be starting the guestbook.”

Ensign Benson gave him the old gimlet eye. “You knew we were coming. You knew how many of us and where we were from and our mission. Somebody had to tell you all that.”

“Easy,” Hank said, grinning. “The stars told us.”

![]()

The town was small but busy, with a bustling, shop-filled main street, Nero-powered surreys and wagons everywhere, and an aura of prosperity and contentment.

“What’s that?” the captain asked as they made their way around a white-stone obelisk in its own little center-of-the-street garden.

“The peace memorial,” Hank said. “We’ve never had anybody to have a war with, but the town plan called for a memorial there—-our ancestors’ original town back on earth had one at that spot—-so about a hundred years ago, they just went ahead and put up a peace memorial.”

People waved as they went by, and a dressed-up reception committee waited out front of the grange hall. “I know you’ve all had breakfast,” Hank said, “but you could probably tuck into some real food. Come on.”

Everybody climbed out of the surrey. Billy Shelby, a happy and innocent smile on his face, said to ensign Benson, “Golly, Kybee, isn’t this place nice?”

“I’m not so sure,” the ensign muttered, glowering at all those happy people. “Keep your eyes open, Billy. There’s something wrong here.”

It was a gala breakfast, laid on just for the visitors and with nearly 50 of the most prominent local citizens in attendance. The Terrans were introduced to, among many others, the principals of both high schools, three ministers, one priest, four doctors, both judges, the police chief, the editors of both newspapers…. Oh, the list went on and on. Then they all sat at long trencher tables under crepe-paper decorations of umber and sienna—Earth colors— and happy chitchat filled the hall as the food came out.

Real eggs. Real homemade bread with real butter. Real bacon. “Hester,” Councilman Luthguster said, “this is what coffee tastes like.”

“Not my coffee,” said Hester.

“I know,” said the councilman.

![]()

“How do you like the breakfast?” Hank asked.

“Fine,” said Ensign Benson, though, in fact, it was all as ashes in his mouth. Looking up, he noticed the designs painted high on the walls, just under the ceiling, 12 on each side, six along each end. Beginning at the front left, three designs incorporated rams’ heads, three involved bulls, then…. “The zodiac,” Ensign Benson said.

“You know it, then.” Hank Carpenter seemed pleased.

“Astronomy. Publius Nigidius Figulus wrote on astrology.”

“One of the great early scholars in the science.”

Ensign Benson raised such a skeptical brow. “Science?”

Hank offered such an indolent chuckle: “You’re from Earth, of course,” he said, “where it doesn’t operate as efficiently.”

“Oh, really?”

“If you were to take an ordinary chemistry-lab experiment,” Hank suggested, “and try it under water, the results wouldn’t please you. Would that disprove the science or reflect the surroundings?”

“So what makes this place better surroundings than Earth?”

“To begin with,” Hank said, “our being at the center of the universe means there’s no distortion. Then, our year is precisely three hundred sixty days long, so we don’t have to keep eternally adjusting things. And Ptolemy’s system includes ten planets, and our planet has two moons and our sun; twelve. One heavenly body per house.”

“Oh, but you can’t seriously—-”

“As the bumblebee said to the physicist,” Hank said, “All I know is, it works.”

![]()

The extremely beautiful blond girl to Billy’s left said, “Hi, I’m Linda. What’s your sign?”

“Billy.”

“Billy? No, that’s your name. When were you born?”

“About three-thirty in the morning,” Billy said. “Mom said everybody’s born at three-thirty in the morning. Can that be right?”

Linda thought about that. She had beautiful violet eyes. “You were born in July,” she decided and turned to talk to the person on her other side.

![]()

Ensign Benson ate toast, eggs, bacon, waffles; but he did not, in fact, taste a thing. He was thinking too hard. “If astrology works,” he said, “it rules out free will.”

“Not at all,” said Hank. The heavens don’t say certainly thus and so will happen, or everybody born at the same time in the same general area would be identical. Astrology deals in probabilities. For instance, the astral alignment so strongly suggested Earth would make fresh contact with its Lost Colonies now that we pretty well discounted any other possibility, but as to the exact make-up of the crew, there were some details we couldn’t be sure of.”

“Still,” Ensign Benson said, “you’re telling me you people can read the future.”

“The probabilities,” Hank corrected.

![]()

“Of course,” Pam Stokes said, an actual real piece of bacon in one hand and her ever-present slide rule in the other, “there are many ways to define the center of the universe.” She bit off a piece of crunchy bacon.

“Oh, sure,” Jim Downey agreed. “And they all work out to be right here.”

Pam frowned, “This doesn’t taste like bacon.”

“Something wrong?”

“No, its—-Actually, its better.”

Putting the slide rule down, she picked up a fork and had at the scrambled eggs.

Pointing, Jim said, “ What is that little stick, anyway?”

“This slide rule? It’s a sort of calculator, used before the computer came in.”

“Like the abacus?” Jim picked it up, pushed the inner pieces back and forth, watched the little lines and numbers join and separate.

“I guess so,” Pam said, reaching for the toast, pausing in amazement when the toast flexed. “It was my mother’s,” she explained, “and my mother’s mother’s, and my mother’s mother’s mother’s and my mo—–”

“Very interesting,” Jim said and put it down.

![]()

Ensign Benson, lost in thought, had stopped eating. “If you’re done, “ Hank said, “We’ll show you to your house.”

The ensign looked at him. “My house?”

“You and your friends. We thought you’d probably all want to live together at first until you get to know the town, make friends, find employment—-”

“Wait, wait a minute.” Ensign Benson was almost afraid to phrase the question. “How long do you expect us to stay?”

“I’m sorry,” Hank said, “You haven’t read your chart, of course. You’ll be here forever.”

![]()

Give Councilman Luthguster a crowd, hell make you a speech. “Earth can do much better for the people of Figulus.” He declared to the local citizens assembled at his table. “Technology, trade agreements. A chicken in every pot; a, a, a, a horse in every stable. Peace, prosperity—-”

“We’ve got all that,” said a citizen.

“And a stable buck,” said another.

Councilman Luthguster paused in mid-flight. “Buck? A stable buck?” Visions of deer, all with symmetrical antlers, leaped into his head.

“That’s our unit of currency,” a citizen explained. “We have the quarter-buck, half-buck, buck, five-buck, sawbuck, all the way up to the C-buck and the grand-buck.”

“And its stable,” another said. “Been a long time since there was a drop in the buck.”

“It entered the language idiomatically,” said a citizen who happened to be a high school principal. “Pass the buck, for instance, meaning to pay a debt.”

“Buck the tide,” offered another.

“That’s to throw good money after bad.”

“Buck and wing.”

“To buy your way out of a difficult situation.”

The councilman stared, pop-eyed. “But that’s all wrong!”

A friendly citizen patted his hand. “You’ll learn them,” she assured him. “Won’t take long—a strong-willed Leo like you.”

“Oh no.” The councilman was firm on that. “How happy I am I’ll never have to learn such gibberish.

His audience just smiled.

![]()

“If your stars tell you we’re staying here,” Ensign Benson said, “they’re crazy.”

“Look, friend,” Hank said. “What if the billions and billions of human beings scattered across the Galaxies were to learn that right here, smack in the middle of it all, was a place where they could find out almost everything about the future? What would happen?”

“You could do a great mail order business.”

“They would come here,” Hank said. “In their billions. Our town would be destroyed; our way of life would simply come to an end.”

Reluctantly, Ensign Benson nodded. “It could get difficult.”

“And that’s why the stars say you’ll remain here and never expose us to the rest of the human race.”

“Sorry,” the ensign said. “I understand your feelings, but we have our own job to do. We just can’t stay.”

“But you will,” Hank said apologetically but firmly. “You see, there’s an armed guard at your ship right now, and there will be for the rest of your lives.”

Odd how easily the next month flowed by. Billy Shelby got a paper route and a job delivering for the supermarket. Pam became a substitute math teacher at one of the high schools, where the male students could never figure out what she was talking about but flocked to her class anyway. Captain Standforth, roaming the country side with his stun gun, brought back many strange and—to him— interesting new birds to stuff. Councilman Luthguster took to hanging around down at city hall, and Hester Hanshaw became a sort of unofficial apprentice at the neighborhood smithy.

Socially, the local belief that ‘those who sign together combine together’ made it easy to meet folks of similar interests. Herds of hefty Taurians took Hester away for camping trips, Billy joined a charitable organization called Caring Cancers, a Piscean gardening-and-water-polo club enrolled Captain Standforth, Pam linked up with the Friends of the Peace Memorial (an organization devoted to maintaining the patch of flowers and lawn around said memorial) and Councilman Luthguster joined the local branch of Lions Club Intergalactical.

Only Ensign Kybee Benson failed to make the slightest adjustment. Only he sat brooding on the porch of their nice white-clapboard house with the green shutters. Only he resisted the overtures of his sign’s organization (the Scorpio Swinging Singles Club). Only he failed to learn the local idioms, take an interest in the issues raised by the morning and evening newspapers (which gave the following day’s weather, with perfect accuracy), involve himself in the community. Only he refused to accept the reality of the local saying that meant the end of negotiation, parley, haggling. The buck stops here.

![]()

“Buck up, Kybee,” Billy said, coming up the stoop.

“What?” Ensign Benson, in his rocking chair on the porch, glared red-eyed at the returning delivery boy. “What is that supposed to mean in this miserable place?”

“Gee, Kybee,” Billy said, backing away a little, “the same as it does back on Earth. It means ‘be cheerful; look at the sunny side’”.

“What sunny side? We’re trapped here, imprisoned in this small town for the rest of our—-”

“Garr-rraaaghhh!” Ensign Benson announced, leaped to his feet and chased Billy three times around the block before his wind gave out.

![]()

Somehow, the second month was less fun. The area round about Centerville had shown to Captain Standforth its full repertory of birds; the board of aldermen would let Councilman Luthguster neither deliver a speech to them nor (as a non-citizen) run for office against them; the high school boys, having grown used to Pam’s useless beauty and having realized none of them would ever either claim her or understand her, now flocked away from her classes; at the supermarket , Billy was passed over for promotion to assistant produce manager; and a Nero kicked Hester in the rump down at the smithy, causing her to limp.

On the social side, things weren’t much better. Hester found her biking Taurians too bossy and quit. Caring Cancers met every week in a different members home to discuss, over milk and gingersnaps, possible recipients for its good works but so far hadn’t found any, which made Billy feel silly. The captains gardening-and-water-polo club kept postponing its meetings, necessitating constant rounds of messages and plan reshufflings. No two Friends of the Peace Memorial could agree on a flower arrangement. And Councilman Luthguster, after a hard-fought campaign in which he had taken an extremely active part, had been blackballed at the Lions Club.

More and more, the former space rovers hung around the house, vaguely fretful. The bilious green sky, the nasty sun (color of ochre juice), the two mingy little marble moons in the eccentric orbits all pressed down on the landscape, on the town, on their own little gabled house, with its squeaking floors and doors that stuck. The local citizens had brought from the Hopeful all their personal possessions—cloths, tools, video camera and monitor, the captain’s birds, Pam’s sky charts Billy’s collection of the Adventures of Space Cadet Hooper and His Pal Fatso and Chang, Ensign Benson’s folders of Betelgeusean erotica, the bound cassettes of Councilman Luthguster’s speeches to the Galactic Council (with the boos edited out), even Hester’s coffee mug—but all these things simply reminded them of their former lives, made their present state less rather than more bearable.

Centerville was a small town in no nation. Distractions were few and local. No movies or videos, only the Morning Bugle and the Afternoon Independent for reading matter, very little variety in clothing or food (all good, all stolid) and no real use for any of their skills or talents. In 500 years, the population had grown from the original 63 to just over 11,000, but 11,000 aren’t very many when that’s all there are.

Even the news that both high school bands would march in next month’s Landing Day parade didn’t lift their spirits a hell of a lot. That’s how bad things were.

![]()

Ensign Benson brooded alone in his rocking chair on the front porch, watching the world (hah!) go by, when a bit of the world in the person of mayor Hank Carpenter came up onto the stoop to say, “Hey, Kybee.” The ensign gave him a look from under lowered brows. Hank cleared his throat, a bit uncomfortable. “We’re sending an ambulance,” he said.

“You’re what?”

“Sorry,” Hank said, looking truly sorry, “but we’ll be taking the captain over to the hospital for a while.”

“What for?”

“Well, uh, he’s about to commit suicide.”

Ensign Benson stared. He knew these people now; they didn’t lie and weren’t wrong. But the captain? He said, “I thought I’d be the first to snap.”

“Oh, no,” Hank assured him. “In fact, you’ll, uh, be the last.”

“That’s it,” Ensign Benson said. Rising, he pointed a stern finger at Hank. “Keep your ambulance. We’ll take care of our own.”

“Well, if your sure you—-”

But the ensign had gone into the house and slammed the door.

![]()

He found the captain upstairs in his room, fooling with a rope. “Come downstairs,” he said. “Now.”

In the kitchen Billy and Hester were making coffee—separately, in different pots. The ensign and the captain entered and the ensign said, “Watch him. If he starts drinking anything funny, stop him.”

Billy said, “You mean, like Hester’s coffee?” But the ensign was gone.

Soon he was back, with Pam and the councilman. “Its time,” he told them all, “to quit fooling around and get out of here.”

“But, Kybee,” Billy said, “we can’t. These people know the future, and they say we’ll never leave.”

“Probabilities,” The ensign corrected him. “The future is not fixed, remember? There’s still free will. The probabilities are caused by our narrowing free will. Things will probably happen in this way or that way because we are who we are, not because the stars force us into anything.”

Hester said, “I don’t see how that helps.”

“We have to break out of the probabilities. Somehow or other—I don’t see it clearly yet, but somehow or other—if we do what we wouldn’t do, we’ll get out of here.

Pam said, “But what wouldn’t we do?” The ensign gave her a jaundiced look. “I know what you wouldn’t do,” he said. “But I would do it, so that’s that. No, we need something that’s so far from the probabilities that, that…”

The others watched him. Ensign Benson seemed to be reaching down far inside himself, willing a solution where there was none. “Take it easy, Kybee,” Billy said.

Hester said “Do you want some coffee? Billy’s coffee.”

Slowly, the ensign exhaled; it had been some time since he’d breathed. “I know what were going to do,” he said.

![]()

“No!” said the captain. “I won’t!”

“That’s the point,” Ensign Benson said.

Hester said, “There’s no way your going to get me to do a thing like that.”

Pam said, “Kybee, this is just a scheme of yours; I can tell.”

“Gosh, Kybee,” said Billy.

“My dignity,” said the councilman.

“Precisely!” Ensign Benson said. “Your dignity is what keeps the probabilities all lined up in a neat and civilized and predictable row. It’s the only way were ever going to get back onto the Hopeful. Think about it.”

They thought about it. They hated it. But that, of course, was the point.

![]()

“Hidy, Kybee. The captain feeling better?”

“Oh, we’ll all adapt, Hank.”

“What’s that you’re watching?”

“Just a little video I made of the captain shooting birds. Never saw one of these machines?”

“No, sir, can’t say I have.”

“They’re easy to operate. Come here, Ill show you.”

![]()

One nice thing about knowing the future, you never have to worry about a rain date for your parade. The sun shone bright, the bands and the marchers were resplendent, and this year, thanks to the Earthpeople, there would be a permanent record of the whole affair! Hank Carpenter, armed with the video camera, stood atop a wagon right down by the Peace Memorial, ready to tape the whole show.

And a real nice show it was. The South Side High School band led off, in uniforms of scarlet and white, and the North Side High School band, in blue and gold, brought up the rear. In between were contingents of the 4-H, the Grange, the police department, bowling leagues, volunteer firemen, a giggle of beauty-contest winners in a bedecked surrey; oh, all sorts of interesting things.

Including the crew of the Hopeful. Naked.

![]()

“Keep taping!” Ensign Benson yelled at Hank Carpenter. “Tape! Tape!” And he did, and they all looked at the tape later, and it was still impossible to believe.

What an array of uncomfortable-looking people. What a variety of flesh was here on display. What an embarrassment all the way around.

Captain Standforth and Hester appeared first, side by side but determinedly separate. The captain sort of vaguely squinted and blinked, pretending to do difficult math problems in his head, while Hester marched along like an angry rhinoceros, daring anyone to tell her she was naked. The captain in the buff looked more mineral than animal: an angular, gawky armature, a scarecrow that wouldn’t scare a wren, an espalier framework for no known tree. Hester, on the other hand, merely became more Hester: chunky, blocky, squared-off.

A rosy astrogator came next: Pam Stokes blushing from nipple to eyebrow, accompanied by an ashen legislator. Councilman Luthguster, shaped very much like the balloons being carried by some of the younger spectators, appeared to have been drained by a vampire before leaving the house that morning. Upon this pallid sausage casing, the hobnails of embarrassed perspiration stood out in bold relief. Would he faint, or would he make it to Main Street? He suffered from the loss of his pomposity much more severely than the simple loss of his clothes.

Pam suffered from the loss of clothes. She was beautiful, but she didn’t want to be beautiful; she was graceful, but she didn’t want to be graceful; she was a treat, but the last thing on Earth—or Figulus—that Pam Stokes wanted to be was a treat. Her expression was like that sometimes seen in dentist’s offices.

Finally there came Billy and the ensign, and here the mark of the ensign’s determination really showed itself. Although it would certainly be embarrassing for him or for Billy to appear naked in public, it wouldn’t, in truth, be quite the horror it clearly was for the others, so for himself and Billy the ensign had escalated the attack .

They were dancing.

Arm in arm, the ensign leading, Billy following pretty well, they turned and turned in great loops, waltzing to John Philips Sousa’s The Thunderer—not impossible but not easy.

Nobody stopped them; nobody knew what to do but stand and gape. For two blocks past the astounded populace, down Broadway from Elm past Church to Main—that being the reach of the video camera—the captain paced, the chief engineer plodded, the councilman trudged, the astrogator inadvertently and unwillingly promenaded and the lieutenant and the ensign waltzed. At Main, surrounded by a populace still immobilized by disbelief, they broke and ran for it, around behind the crowd, through back yards and alleys and away. With many a hoarse cry and broken gasp, this unlikely herd thundered all the way home, up the stoop, across the porch, into the house and slammed the door.

![]()

Knock, knock.

“Who’s there?”

“Hank Carpenter, Miss Hanshaw. You folks all right in there?”

“Go away.”

“It’s been five days; you can’t just—-”

Hank waited. He went over and sat on the porch railing and looked out at the sunny day. The rubbernecks who had filled this street at first had given up by now, and everything was back to normal. But what had it all been about, anyway?

This was one of those rare moments when the charts didn’t help. If it were simple madness, of course, that would explain a lot, since insanity can play merry hob with your probabilities, but somehow Hank didn’t believe lunacy was the answer.

The front door opened and Ensign Benson came out, carrying a thin folder. He shut the door behind himself, gave Hank a quick, nervous smile, then frowned out at the street.

“They’ve all gone,” Hank assured him.

“I didn’t know it would be quite that bad,” the ensign said. “It does something to your nervous system to be naked in front of that many people.” He had a twitchy look to him and didn’t quite meet Hank’s eye.

“What we can’t figure out is why you did it.”

“So you could let us go, of course.”

Hank smiled in confusion. “You mean, we’d take pity on you because you lost your minds?”

“We didn’t lose our minds, just our clothes. You’ve got it all on tape, right?”

“I don’t know why you’d want such a thing,” Hank said, “but yes, we do.”

“Look at this,” Ensign Benson said, extending the folder.

Hank took it, opened, found himself reading a report to the Galactic Council about the lost colony known as Figulus. “Says here, the settlement was abandoned. Colonists long dead. Some unanticipated poison in the atmosphere.”

“Not suited for human life,” the ensign said. “As soon as were aboard ship, that’s the report we’ll send.”

“Why?”

“You’re keeping us here because your afraid well spread the news about you and a lot of people will show up to learn all about the future.”

Hank nodded. “Destroying our future in the process.”

“If anybody did arrive, the ensign said, “you’d blame us. You’d probably be mad enough to show that tape.”

“I’m beginning to see the light,” Hank said. “You were looking for a way to bust loose from the probabilities.”

“That’s right. What could we do that we wouldn’t do?”

“Walk down Broadway at high noon, naked, with a brass band.”

“As long as you have that tape,” Ensign Benson said, “we’ll do anything—anything—to keep the rest of the human race away from here.” Wanly he smiled. “And if this doesn’t work,” he said, “if you still won’t let us go, we’ll just have to get more improbable.”

“How?” Hank asked, a bit wide-eyed.

“I don’t know yet,” the ensign told him. “I hope I never know. How about you?”

Out, out, out across the illimitable void soared the Hopeful. Its crew, garbed in every piece of clothing they owned and not looking one another in the eye, had left Figulus without even having their charts done. They knew nothing of the future.

Just as well.

Copyright © 1985 by Donald Westlake