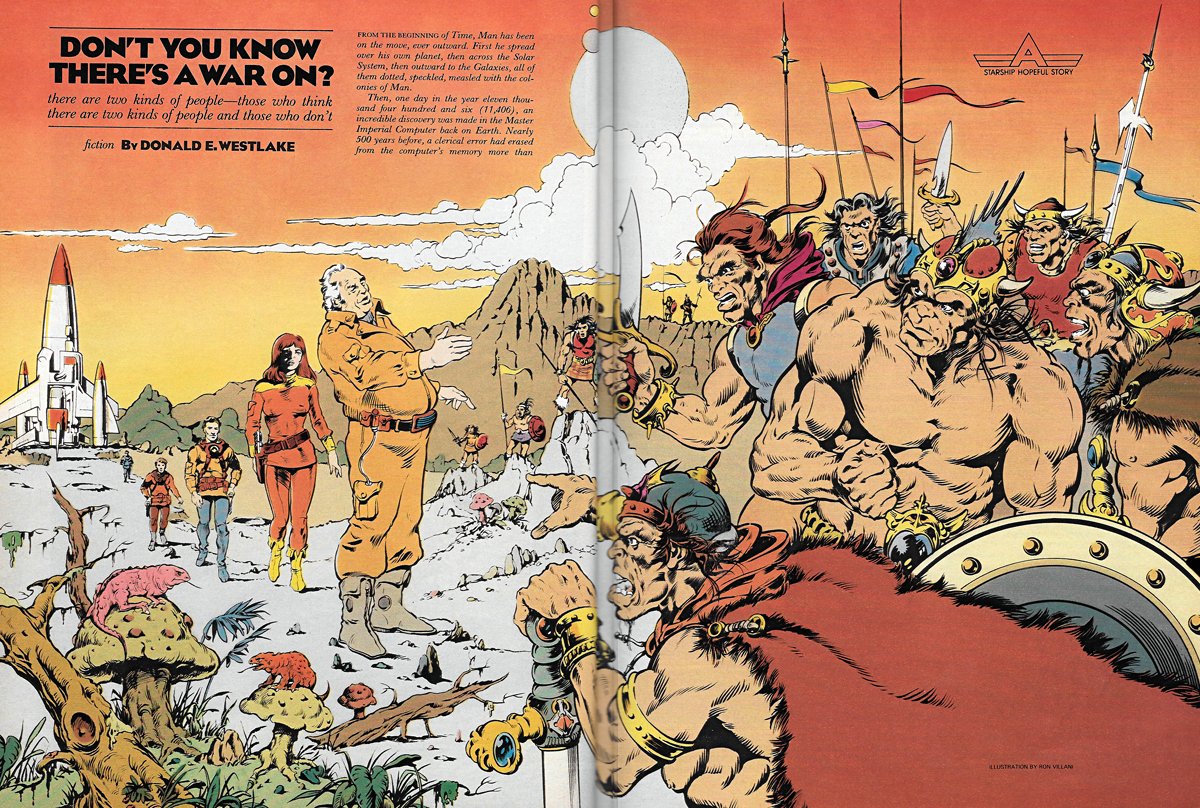

Don’t You Know There’s a War On?

The two armies were massed in terrible array, banners flying, the hosts facing each other across the verdant valley. The tents of the generals were magnificently bedecked, pennons whipping in the breeze. Down below, clergymen in white and black blessed the day and the pounded grass and the generals and the banners and the archers and the horses and those who sweep up behind the horses. Filled with a good breakfast, the soldiers on the slopes stood comfortably, happy to be a part of this historic moment, while the supreme commanders of both forces marched with their aides and their scribes down through their respective armies and out across the green sweep of neutral territory toward the table and the altar set up in the very center of the valley under a yellow flag of truce.

This was the first time these two supreme commanders had met, and they studied each other with a pardonable curiosity while the various aides exchanged documents and provided signatures. Is he fiercer-looking than me? the supreme commanders wondered as they eyed each other. Is his jaw firmer and leaner? Do his eyes flash more coldly and cruelly? Is his backbone more ramrod-stiff?

The ministers sprinkled holy water over the papers. The supreme commanders firmly shook hands–very firmly shook hands–and a great cheer went up from the multitudes on the slopes. The ceremony was complete. The name had been changed. The 300 Years’ War was now officially the 400 Years’ War.

“Look out!” someone shouted.

Soldiers gaped. Horses neighed and pawed the ground. Clergy and aides fled with cassocks and tunics flapping, Supreme commanders took to their heels and the great long silver bullet of the spaceship settled slowly, delicately, almost lazily into the very center of the valley, the massive base of the thing gently mashing the main altar into a dinner mat.

![]()

“Remember, Councilman,” Ensign Kybee Benson said, pacing the councilman’s cabin, “these are intelligent and subtle people, the descendants of philosophers.”

“Hardly a problem,” Councilman Morton Luthguster responded. “I’m something of a philosopher myself.”

Ensign Benson and Councilman Luthguster meshed imperfectly. Ensign Benson was almost painfully aware that the reason the councilman had been chosen to represent the Galactic Council on this endless, trivial, boring mission to the universal boondocks was simply that nobody at the Galactic Council could stand the man’s pomposities anymore. Luthguster didn’t realize that; nor did he realize that it was Ensign Benson’s sharp-nosed personality that had won him a berth on the Hopeful (neither did Ensign Benson); but he’d certainly noticed that all his conversations with Ensign Benson left him with the sense that his fur had been rubbed the wrong way.

Ensign Benson’s face now wore the expression of a man eating a lemon. “Councilman, would you like to know which particular philosophy these philosophers philosophized about?”

“You’re the social engineer,” Luthguster pointed out, getting a bit prickly himself. “It’s your job to background me on these colonies.”

“Dualists,” Ensign Benson said. “They were dualists.”

“You mean they fought each other.”

Lieutenant Billy Shelby, the Hopeful’s young second in command, knocked on the open door and entered the cabin, saying, “Sir, the ship has landed.”

“Just a second, Billy.” Taking a deep breath, displaying his patience, Ensign Benson said, “Not duelists, Councilman, dualists. They believed in the philosophy of dualism. Simply stated, the idea that there are two sides to every story.”

“At the very least,” Luthguster said. “Back in the Galactic Coun—”

“Gemini,” Ensign Benson interrupted. “That’s what they named their colony, after the twins of the zodiac. They’d originally considered Janus, after the two-faced god, but that suggested a duplicity they didn’t intend. Discussion and debate; that’s the core of their approach to life.”

“A civilized and cultured people, obviously.” Luthguster preened himself, patting his big round belly. “We shall get along famously.”

“No doubt,” Ensign Benson said. “Shall we begin?”

They followed Billy Shelby down to the main hatch, where the ladder had already been extruded, but the door was not yet open. Waiting beside’ it was Captain Standforth, tall and thin and vague, his stun gun ready in his hand. Pointing to the weapon, Luthguster said, “We won’t be needing that, Captain. These are peaceful scholars.”

“I thought I might shoot some birds,” said the captain. “For stuffing.” Bird taxidermy was the only thing in life the captain really cared about. Seven generations of Standforths had, unfortunately, made such magnificent careers in the Galactic Patrol that this Standforth had had no choice but to sign up when he’d attained the proper age, but the whole thing had been a ghastly mistake, which everybody now knew–and which was why he had been assigned to the Hopeful.

“Shoot birds later,” Luthguster said, somewhat stiffly. “Let us begin peacably. Open the door, Billy.”

Billy pushed the button, the door opened and Luthguster stepped out onto the platform at the head of the ladder. ‘Fellow thinkers,” he cried out and fell back into the ship with seven arrows stuck in him.

![]()

“Rotten aim,” Chief Engineer Hester Hanshaw said, wiping her hands on a greasy rag, then dropping it onto the cluster of pulled arrows. “You’ll live.”

“At least you could sound happier about it,” Luthguster told her. Lying here on the engine-room table, he was so enswathed in bandages that he looked like a gift-wrapped beach ball.

“It’s mostly all that blubber protected you,” Hester said unsympathetically. “You’re a very inefficient design.”

“Well, thank you very much.”

There was no doctor on the Hopeful, there being room for only five crew members and the councilman. Hester Henshaw, 40ish, blunt of feature and speech and hand and mind, had taken a few first-aid courses before departure, with the attitude that the human body was merely a messier-than-usual kind of machine and that most of its ills could be repaired with a few turns of a screwdriver or taps of a hammer. (Pliers had been useful in the current case, plucking the arrows out of the councilman.) Hester never gave her engines sympathy while banging away at them, so why should she give sympathy to Luthguster? “I’ll give you some coffee,” she offered grudgingly.

Luthguster knew Hester’s coffee from hearsay. “No, thank you!”

“Don’t worry, you won’t leak. I plugged all the holes.”

Luthguster closed his eyes. A moan leaked out.

![]()

Lieutenant Billy Shelby, handsome, romantic, idealistic, bright as a bowling ball, clutched the microphone in his left hand, white flag in his right, and said, “Ready, sir.”

The captain hesitated. “Are you sure, Billy?”

“He already volunteered, Captain,” Ensign Benson pointed out. “Obviously we have to make contact with the Geminoids somehow.”

“I’m sure, Captain,” Billy said.

So the captain pushed the button, the door opened and Billy marched out onto the platform with the white flag high and the loud-speaker microphone to his mouth: “People of-” his voice boomed out over the valley, and a cannon ball ripped through the white flag to carom off the silver hull.

Billy gaped at the hole in the flag. “Gee whizz,” his amplified voice told the sunny day. “Don’t you guys believe in a flag of truce?”

“That ain’t no flag of truce!” a voice yelled from upslope. “It’s white!”

“Well, what color do you want?”

“Yellow! The color of cowards!”

“Wait right there,” Billy told the two encircling armies and went back into the ship. Carom! went a cannon ball in farewell.

![]()

“After dark,” Supreme Commander Krraich said, “we’ll deploy a patrol to sneak up on the thing and set fire to it.”

“I suspect, sir,” said an aide carefully (Krraich was known to dislike correction), “the thing is made of metal.”

Krraich glowered. Sneaking up on things and setting fire to them was one of his favorite sports. “It’s a fort, isn’t it?” he demanded. “Could be just shiny paint.”

“Sir, uh, cannon balls bounce off.”

“Doesn’t mean it’s metal. Could be rubber.”

“Rubber won’t burn, sir.”

Krraich turned his gaze full upon this pestiferous aide, whose name was Major Invercairnochinchlie. In the bloodshot eye of his mind, Krraich watched Major Invercairnochinchlie burn to the ground — kilt, sporran, gnarled pipe, tam and all. “What do you suggest, Major?”

Invercairnochinchlie swallowed. “Acid, sir?”

The other aides, also in formal officers’ kilts, all snickered and shifted their feet, like a corralful of miniskirted horses; aides liked to see other aides in trouble. But then, Krraich’s least favorite and most intelligent aide (the two facts were not unconnected), a colonel named Alderpee, said, “Sir, if I may make a suggestion?”

“You always do,” Krraich said, irritated because the suggestions were usually good.

“That thing out there is a fort,” Aldepee said. “A traveling fort. Think how we could use such a thing.”

Krrairh had no imagination. “Your suggestion?”

“They’re about to send out a party under a flag of truce. We kidnap that party, apply torture and learn how to invade the fort. Then we take it over.”

Krraich was appalled and showed it. “Violate a yellow flag of truce?”

“Those people aren’t a part of our war,” Alderpee pointed out. “They’re innocent bystanders. The rules of battle don’t apply.”

“Ah,”

“And if we don’t do it,” Alderpee added, “the Antibens will.”

![]()

“How do you do? I’m Lieutenant Billy Shelby of the Interstel — Mmf!”

![]()

“There!” Colonel Alderpee cried. “I told you the Antibens would do it”

![]()

The chaplain, in his black dress uniform, sprinkled holy water over Billy, who sneezed. “Gesundheit,” said the chaplain.

“Thank you.”

“I am the Right Reverend Beowulf’ Hengethorg,” the chaplain explained. “I am here to ready you for torture.”

“Torture?” Billy gaped around at all the big, mean-looking, bulgy-armed men lining the periphery of the large, torchlit tent. “Gee whizz,” he said, “we’re here to be friendly. We came all the way from Earth just to-”

“Earth?” Wide-eyed, Reverend Hengethorg leaned close. “You wouldn’t lie to a reverend, would you?”

“Oh, no, sir You see, you were lost, and-”

“And on Earth,” the chaplain said, voice tensely trembling, “do they believe in Robert Benchley?”

![]()

“I’m the only possible volunteer. The councilman is wounded, Hester keeps the engines going, Pam Stokes astrogates and you understand the mission. I’m not necessary at all.”

“Well, Captain,” Ensign Benson said as they strode doorward together, “I have to admit you’re right. All captains are unnecessary; you’re one of the rare ones who know it.”

“So I’ll try to make peace with the other army,” the captain went on, “and ask them to help us rescue Billy.”

“And find out what’s going on here.”

“Well, I’ll certainly ask,” the captain said.

They had reached the door, where firmly the captain pushed the button. “There’s no point in carrying any flags,” he said. “These people don’t seem to respect any color.” He stepped outside.

“Good luck, Captain.”

The captain looked back over his shoulder. “Did you say some-” He dropped from sight. Thump crumple bunkle bong kabingbing thud.

Ensign Benson leaned out. to gaze down at the captain, all in a heap at the foot of the stairs. “I said, good luck.”

![]()

“Another one!” cried Colonel Alderpee. “Men, get that one or we’ll be using your heads for cannon balls!”

![]()

“The ultimate proof” the Right Reverend Hengethorg was saying. “This fine young chap here has never even heard of Robert Benchicy, much less read his work.”

Proud of his ignorance, Billy smiled in modest self-satisfaction at Supreme Commander Mangle. “That’s right, sir. What I mostly read is The Adventures of Space Cadet Hooper and His Pal Fatso.”

![]()

Supreme Commander Mangle, a knife of a man — a tall, glinty-eyed, bony, angry knife of a man — growled deep in his throat; a distant early warning. Billy blinked and decided after all not to give the supreme commander a plot summary of Cadet Hooper and His Pals Go to Betelgeuse.

Mangle turned his laser eyes on Hengethorg. “Reverend,” he said. His voice needed oiling. “Explain.”

“The people of Earth are Antibens like us,” the chaplain explained. “Must be! Not only does that prove the truth of our philosophy but we can ally ourselves with Earth and destroy the Bens, forever!”

Mangle brooded. Apparently, he was considering the advantages and disadvantages of allying himself with people like Billy Shelby, because when next he asked, “Are there any more at home like you?”

![]()

“So you’re from Earth,” Colonel Alderpee said.

Yes, I am,” Captain Standforth told him. “I’m terribly sorry, but would you mind scratching my nose? Just the very tip.” The captain had been tied with a lot of rope immediately upon arriving in this army’s camp, so now his fingers (and their nails) were imprisoned behind him.

Colonel Alderpee at first looked confused, then seemed on the verge of scratching the captain’s nose, then obviously bethought himself and snapped to several nearby soldiers, “Untie this man, I believe there are enough of us quell him if necessary.”

“Oh, I won’t need quelling,” the captain promised. “Just scratching.”

So the ropes were removed and the captain indulged in a good scratch while Colonel Alderpee went off to consult with Supreme Commander Krraich and a couple of chaplains in a far corner of the tent. Returning a minute later looking as though his own nose were now a bit out of joint, he said, “Well, Captain Standforth, I wouldn’t do it this way–I think it’s a waste of time–but before we get to the subject of our conversation, I am required to ask, you, an absolute alien, your position on the Benchley Paradox. So listen carefully.”

The captain listened, idly scratching his nose (now more for fun than for need).

“There are two kinds of people in the world,” Colonel Alderpee began.

“This world?” the captain asked. “Or Earth?”

“Any world! This is the Benchley Paradox; now, listen.”

“I do beg your pardon.”

“There are two kinds of people in the world,” the colonel repeated. “They are, Robert Benchley claimed, those who believe there are two kinds of people in the world and those who don’t believe there are two kinds of people in the world. Now. Do you agree with that?”

“Absolutely,” the captain said. “Seems perfectly clear to me.”

Ensign Benson did not entirely believe it. Billy and the captain were both back, and each had made a tentative alliance with the locals — with different sets of locals. Upon their return, Ensign Benson had brought them both up to the command, deck and, while the wounded councilman and Hester and even the usually distracted Pam had all sat around listening, he had questioned both ex-prisoners. Their stories had dovetailed so thoroughly that Ensign Benson really had no choice but to accept the reality. “They are fighting,” he said at last, “over Robert Benchley,”

“A philosopher, I guess,” Billy said, scratching his head.

“Very important, anyway,” the captain added, scratching his nose.

“A smart-aleck, to judge from his paradox,” Ensign Benson said. “Perhaps even, a deliberate humorist,”

“Dangerous people, humorists,” Luthguster opined. “They should not be taken lightly.”

All around, the captain’s stuffed birds glared down from their perches, unwinking glass eyes peering from among feathers and beaks and claws of every color in the rainbow and a few colors outside the known rainbow of Earth. “All right,” Ensign Benson said. “I begin to see what happened. One of those original philosopher settlers, with that heavy-handed light touch professors love so well, introduced the Benchley Paradox, in which you prove Benchley right by disagreeing with him. Because if everybody agreed with the paradox, then there’d be only one kind of person in the world, and the paradox would be wrong. Are any of you pinbrains getting this?”

“Certainly,” said Luthguster, while the captain and Billy and Hester shook their heads and Pam doggedly worked her slide rule. The stuffed birds gaped down as though the very thought of the Benchley Paradox made them furious.

“The Gemini philosophers,” Ensign Benson went on, “had found a topic without the usual comforting weight of precedent behind it. Rather than cite old texts at one another, they were forced to think for themselves. Unable to appeal to prior authority, they couldn’t end the quarrel at all. Each succeeding generation became more rigid and less scholarly, until, by now—”

“Total war,” Luthguster finished, demonstrating his grasp of the situation.

“They sure don’t like each other much,” Billy agreed. “Boy, what they said about the Bens.”

“The Bens said some things, too,” the captain said, as though he felt it his job to defend his side in the war. “About the Antibens, I mean.”

Ensign Benson cleared his throat in a hostile manner. When every person and bird in the room was looking at him, he said, “All right. The first question is, What do they want from us?”

“An alliance,” Billy said. “To help them destroy the Bens,”

“Well, no,” the captain said. “Actually, they want an alliance to help them destroy the Antibens.”

Luthguster sighed, his wounds creaking. “Dealing with one colony at a time is trouble enough,” he said. “When they begin to multiply —”

“Divide,” corrected Ensign Benson. “We’re dealing here with mitosis, not sexual reproduction.”

“Mitosis,” Pam said, looking bright. “I know what that is.”

“You would,” Ensign Benson told her. “All right, let’s concentrate on the problem at hand. Obviously, Earth can’t send technical assistance or start trade programs while this war is going on, so our first job is to bring peace. Any suggestions?”

“Once my wounds heal,” Councilman Luthguster said, “I shall engage in shuttle diplomacy. I’ll speak with the political leaders, deliver their demands, conduct negotiations, and, eventually, I’ll find the happy middle ground where the language is vague enough so each side can believe it has won. Yes.” The councilman gazed radiantly at some wonderful image of himself in the middle distance. ” “The Luthguster Peace,” he quoted from some future history text.

“In the first place,” Ensign Benson said, “there are no political leaders on Gemini. From what Billy and the captain say, the society has been taken over entirely by the two groups of military commanders, with the assistance of the religious establishment. In the second place, this isn’t a war of territory or trade routes or anything else rational that can be negotiated. A war of philosophical difference is something else again. And in the third place, Councilman, I’ve seen you in action with local citizens before, and I don’t want to unite the bloodthirsty factions on Gemini by making them form an alliance against Earth.”

“Well, really,” Luthguster said, indignantly scratching his wounds.

“If you want a thing done right,” Ensign Benson said in disgust, “you have to do it yourself. Unfortunately.”

![]()

“The Right Reverend Beowulf Hengethorg,” Billy said, on his best behavior, “I’d like you to meet Ensign Kybee Benson, social engineer of the Interstellar Ship Hopeful.”

“Ensign,” echoed Reverend Hengethorg, as he grasped Ensign Benson’s outstretched hand in a grip of steel. “Is that a clerical rank, or military?”

“Somewhere between the two,” Ensign Benson said through clenched teeth; it was the first time since elementary school that he’d tried to out-squeeze another person in a handshake.

They were standing in the sunlight outside the large command tent while dozens of men armed with arrows and broadswords and maces and battle-axes and clubs and knives and metal-toed shoes sat around their several other tents, watching the two Earthlings with the flat expressions of carnivores looking at meat.

Ensign Benson had understood it was his job to visit both encampments, being introduced first to the Antibens by Billy and later to the Bens by the captain in his own effort at shuttle diplomacy — or shuttle philosophy. Now, feeling all those martial eyes on him, he reminded himself that this was, after all, the most sensible thing to do under the circumstances; pity he’d been smart enough to know it.

“It was a great moment for us all,” Reverend Hengethorg was saying, as he at last released Ensign Benson’s hand with a little superior smile, “when Lieutenant Shelby confirmed what we have for so long believed: that Earth is firmly Antiben. I may say I took it as a personal vindication.”

“Actually,” Ensign Benson said, massaging his fingers and speaking with caution, “Earth’s philosophical position anent the Benchley Paradox is somewhat more sophisticated than that.

Essentially, I would say Earth’s position encompasses elements of both the Ben and the Antiben points of view.”

Reverend Hengethorg’s frown had something of the Inquisition in it. “Both points of view? How can a position encompass absolute contradictions?”

“Well, we don’t see the Bens and the Antibens as being absolutely contradictory,” Ensign Benson explained.

“They are on Gemini,” the reverend said. “But you must come with me to the chaplains’ tent and explain Earth’s position to the reverend fathers.”

“I’d like that.”

With the smiling, unconscious Billy trailing after, they walked together toward the chaplains’ tent, safely placed on the far side of the slope, and Ensign Benson said, “This is quite a large encampment. How many of your people are here?”

“Why, all of us,” Reverend Hengethorg said in some surprise. “Except for a few spies in the Bens’ camp, of course. Where else would we be?”

“Don’t you have a town? Forts?”

“I don’t know what you mean by town,” the reverend said. “We have had forts, but they were vulnerable to fire and siege and difficult to move, unlike that fort of yours, which we all admire very much.”

“So the women are right here with the army.”

“The women are in the army. We are all in the army.”

“Children?”

“Military school, just over there,” the reverend said, pointing toward a nearby copse from which came the shrieks of childish savagery.

“What about farms? Food?”

“We have our herds. We hunt and we pick fruits and so on in season.”

They walked past a smithy, where metal bits for harnesses were being hammered into shape. “How many of you are there?” Ensign Benson asked.

“That’s a military secret,”

“More than five hundred, I’d guess,” Ensign Benson said, looking around. “Fewer than a thousand.”

“If you say so.” The reverend clearly didn’t like having his military secret guessed at so easily and accurately.

“But as the population grows…”

“Why should it grow?” Gesturing around them, the reverend said, “We and the Bens have had stable populations for four hundred years.”

Ensign Benson nodded. “Birth control?”

The reverend shook his head. “War,” he said.

They had reached the chaplains’ tent. “My colleagues will be delighted to meet with you,” the reverend said. “There’s nothing we all like more than lively philosophical debate.”

“That’s fine.”

“Of course,” the reverend went on, “the liveliest philosophical debates take place under torture. But there’s no question of that here,” he said, holding open the tent flap, smiling wistfully to show how bravely he was taking the deprivation, “is there — Earth being our ally against the Bens.”

“Indeed,” Ensign Benson said and followed Reverend Hengethorg into the tent.

![]()

“Captain,” Pam said, tapping her finger tips against the frame of the cabin’s open door, Captain Standforth looked up. A knife was in his right hand, a palmful of desiccated guts in his left, and a pitiful lump of orange feathers lay before him on the desk, oozing green blood. “Yes, Pam? I’m very busy. I must finish stuffing this Nibelungen nuthatch before it dries out.”

“There’s someone here,” Pam told him. ‘”‘To see you. A man named Colonel Alderpee.”

“Oh, yes,” the captain said, rising, wiping green phlug from his hands onto his uniform jacket. “I told him he could drop by. He was very interested in the ship.”

“He certainly is,” said Pam.

He certainly was. The captain and Pam met him in a corridor well within the ship, one level above the entry port. Colonel Alderpee, looking very happy, was accompanied by a small, skinny scribe who earnestly scribbled notes to the colonel’s directives: “Granaries along here, I think. Horse stalls below; we’ll need straw. Oh, and moat detail to report at fifteen hundred hours.”

Seeing the captain and Pam, Colonel Alderpee said, “Ah, Captain, delighted! It’s a different fort from anything I’ve seen before, but very adaptable.”

“Colonel, what are you”– the captain began, then stopped with a squawk when he saw, ambling around the far corner of the corridor, a purple cow, closely followed by a yellow-and-white polka-dotted dog. “What– What’s that?”

“Eh? Oh, the herd,” the colonel answered.

And it was. It was the herd and the herders and the herders’ dogs and the herders’ wives and children. And the army, with banners, marching to the squeal of bagpipes. And the clergy, with collection baskets, and the cooks and the smithies and the leatherworkers and the teachers and the glee club and the magicians and the stortellers and the horses and the hay and the forges and the whips and the thumbscrews and the tents (folded) and the extra arrow feathers and the cooking pots and the bits of string that might be useful someday and the unfinished wooden statues of horses and the supreme commander, Krraich, who shook the captain’s hand very hard and said, “I shall take command now.”

“Oh, my goodness,” the captain said to Pam. “We’ve got the Bens!”

![]()

Ensign Benson sat on a low stool in the chaplains’ tent, in the midst of the reverend fathers, both hearing them and asking them questions. And what he’d already heard had not been at all encouraging. He’d entered this den of iniquity intending by easy stages to lead the Antibens around to a more open point of view, but he’d soon seen it was hopeless. Never in his life had he met so many firmly closed minds.

Every approach he’d made to broaden the Benchley Paradox had brought angry frowns and mutterings of Heresy. Ensign Benson could imagine — far too well — what happened to heretics on Gemini, so by now he was simply vamping along, trying to figure out some way to get out of there alive. “if we accept the Runyon Postulate,” he was saying, “that all of life is six to five against, as glossed by Sturgeon’s Second Law, that ninety percent of everything is crud, we can then see that Benchley’s Paradox merely acknowledges that there will at all times be unenlightened people who–”

Were they mumbling “Heresy” again, for God’s sake? Was the word blasphemy being bandied about? “What I’m trying to say—” Ensign Benson began again, wondering what he was trying to say, and Billy came into the tent, crying,. “Ensign Benson! Come look!”

“Look?”

“The ship!”

More trouble? “Excuse me,” Ensign Benson told the chaplains. “I must be about my captain’s business.” And he marched right on out of the chaplains’ tent.

To see, down in the center of the valley, the Hopeful filling up with Bens. “Oh, now what?” Ensign Benson cried, at the end of his tether.

“You,” said a knife-thin, harsh-faced resplendently uniformed man pointing a bony finger at Ensign Benson, “shall pay for this treachery.”

“Supreme Commander Mangle,” Billy said, with his party manners again, “may I present Ensign Kybee Benson.”

“Hello,” the supreme commander said. “You die now.”

“Wait a minute! I had nothing to do with that,” Ensign Benson said, pointing at the spaceship. Some clowns down there had started digging a moat. “I’ll take care of it right now.”

Mangle’s thin lips curled. “You expect us to permit you to return to your Fort?”

Ensign Benson looked at Billy, Who sighed but managed a brave little smile. “I know,” he said. “This is where I volunteer to stay as a hostage.”

![]()

“I don’t care who you are,” Hester said. “You can’t start a lot of fires in my engine room.”

“I’m the smithy,” the burly man explained, stacking his firebricks near the reactor, “and the sergeant says this is where I set up.”

“Well, you can tell your ser —”

Ensign Benson entered the engine room. “Hester.”

“Would you tell this–”

“Ssh! Come here!”

So Hester went there, and Ensign Benson said, “Forget him. Start the engines. Don’t worry about a thing.”

![]()

“Billy will be worried,” Pam said.

“Billy will be all right,” Ensign Benson told her. “We’ll all be all right. You just plot the course. As for you, Captain, surely you know how to drive this thing.”

Pam and Ensign Benson and the captain were together on the command deck with a lot of squalling babies; Colonel Alderpee had decreed this space was the nursery. Councilman Luthguster was off making a courtesy call on Supreme Commander Krraich.

“Well,” said the captain doubtfully, “I have driven it, but that was a long time ago.”

“Just take her up,” Ensign Benson said, “and head southeast. Right, Pam?”

“Mm,” Pam said, lost in her slide rule.

![]()

“Build boats,” Supreme Commander, Mangle said. “Tonight, we cross that moat.”

“Sir,” said an aide, coming into the tent, “the fort is leaving.”

They all went outside. The fort was gone. The moat remained, a ring of muddy water around a crushed altar.

“Sir? Do you still want the boats?”

“Kill that idiot,” Mangle said. “And bring me the hostage Earthling.”

![]()

Ensign Benson went to the commander’s tent (a.k.a. dining room) to explain the situation to a suspicious Colonel Alderpee and a glowering Supreme Commander Krraich. “The fort,” the colonel Pointed out, “is moving.”

“Plague,” Ensign Benson said. They stared at him. They recoiled from each other. “Plague! Where?”

“Back where we came from. The ship’s instruments showed there was a breakout just due. Congratulations, gentlemen,” Ensign Benson continued, “you have at last won your war. Within a week, there won’t he a living Antiben on Gemini.”

![]()

Southeast across the surface of the planet ran the Hopeful, guided by Pam’s slide rule and steered erratically by Captain Standforth, who had to keep picking babies out of the controls. Diagonally ran the ship, down from the Northern Hemisphere to the Southern, around from the Eastern Hemisphere to the Western. Exactly opposite the original encampment, in similar climate and terrain, where they would be easy for Earth’s supply ships to find but where they would never again meet their enemies, the Hopeful set down and unloaded the Bens. “You’ve done a fine thing for Robert Benchley,” Colonel Alderpee said as the Bens and their beasts, their tents and their babies all deshipped.

“It was the least we could do,” Ensign Benson assured him. “After all, you had reached a stalemate in what was clearly a war of total extermination. Something had to be done.”

“Peace, it’s wonderful,” the colonel said, then frowned. “At least, I’ve heard it is.”

Councilman Luthguster made a speech promising wonders in aid and technical assistance to come from Earth. Some archers playfully lofted arrows in his direction, but they were only fooling, and the one flesh wound that resulted was easily patched by Hester with a snippet of stickon plaster, meant for stemming leaks in boilers.

“I was beginning to rather like all those babies,” Captain Standforth said, a faraway look in his eye. “I wonder how you… Hmmmm.” He went away, to study his taxidermy books.

![]()

“Plague,” Ensign Benson said, as Billy was untied from the rack. “You’ll never see a living Ben on Gemini again.”

And you took them away,” Reverend Hengethorg said “so they couldn’t infect us.”

“That’s right.”

“You’ve done wonders,”

“I know,” Ensign Benson said.

Billy came over, massaging his chafed wrists. He looked taller. “Gosh, Kybee,” he said.

“Well, ta-ta,” Ensign Benson told the Antibens. “You’ll be hearing from Earth. Our job here is finished now.”

![]()

“Sir,” an aide said to Colonel Alderpee, “there’s a dispute among the men.”

The colonel gazed over the new encampment, the tents still being raised, the thud-thud of posts being driven into the virgin ground. “Dispute? Over what?” “Well, some of the men say those people in the fort were from Earth, and some say they weren’t.”

“Really? Call a meeting. We’re mature adults; we’ll discuss it.”

Copyright © 1981 by Donald Westlake