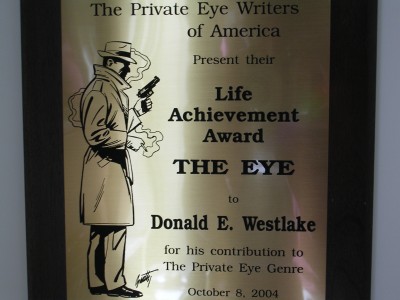

On October 8th [2004] the Private Eye Writers of America gave me their annual Shamus Award [The Eye, Lifetime Achievement Award] at a dinner in Toronto, in conjunction with this year’s Bouchercon. Airplane schedules defeated my plan to be there to accept the award, but I sent along the following acceptance speech, which was read to the group by Bob Randisi. I was not the only one who was there in spirit only. Max Allan Collins introduced me, but he couldn’t be there either, so his astral spirit introduced my astral spirit, or something like that. Anyway, here’s what he said, and then here’s what I said. ~DEW

Donald E. Westlake

by Max Allan Collins

Few writers are more worthy of winning a life achievement award from a mystery writer’s organization than Donald E. Westlake. But in a sense, he is an unusual choice for the PWA’s Eye award.

My childhood fascination with private eyes on TV and later P.I.s in books by Hammett, Chandler, Spillane and others, led me down the mean streets of my career path. But toward the end of my teens, two things happened to me that changed that path, temporarily at least: one was changing times, with the P.I. starting to seem out of step with the turbulent tempo of the late ’60s; and the other was Richard Stark.

Nudged by the film POINT BLANK as adapted from the novel THE HUNTER, I discovered Richard Stark’s Parker character and came to understand that the hardboiled figure who’d been the hero of so many P.I. novels could make a slight lefthanded shift and become…a crook. The same loner stance, and personal code, that made the likes of Spade, Marlowe and Hammer appealing to me — and to readers — could be carried out by, of all things, a thief.

I got so caught up in Parker and Stark that other mysteries and crime novels started seeming flat to me, so I sought a change of pace. Somebody recommended a writer who was turning out quirky comic crime novels, often in the first person, and I tried one of them — THE FUGITIVE PIGEON, I believe — and pretty soon I had two new favorite writers — Richard Stark and Donald E. Westlake. Despite the wild difference in style between these writers, I put their books side by side on the bookshelf in my bedroom (I was still living at home, in my first year of community college).

I believe it was Anthony Boucher who “outed” Westlake. In a New York Times review column of his, I read that these two polar opposites were a single talented writer…and that they were also some other guy named Tucker Coe.

I did the following: picked myself up off the floor; removed the bookend that had previously separated Stark from Westlake on my bookshelf; and went out looking for the Tucker Coe books.

The Coe books — there are just a handful, five — are significant, because Westlake really isn’t very interested in pursuing the P.I. novel as a narrative form. Like me, he had problems with finding a way to write about private eyes in a setting that wasn’t the original ’30s or ’40s. My answer, some years later, was to put the P.I. in a historical framework. Westlake was among the first to put his P.I. in a contemporary setting, bumping him up against grown-up matters like alcoholism, adultery and homosexuality, and even the occasional hippie.

More important, his private eye Mitch Tobin was a troubled man, imperfect — somebody who carried guilt over the death of a partner, due to his own moral failings. In a simple but brilliant device, Westlake set his detective upon the obsessive task of building a wall, brick by brick. The P.I. could never quite hide behind that wall, much less finish it. He did not want to leave his house, but his own basic human decency would occasionally send him out into a recognizable late ’60s/early ’70s urban world, to help people, and scratch his redemptive itch.

Tucker Coe’s style, unlike that of most P.I. writers of the day, was uninfluenced by Chandler — it was simple, and, well…stark. The books dealt with emotion and occasionally sentiment but were unsentimental. Though well-reviewed, they didn’t set the marketplace on fire…but scores of writers who followed Tucker Coe were influenced by this approach. Westlake’s longtime friend Larry Block is perhaps the most successful of many who saw in Tucker Coe a contemporary, more realistic way to write about P.I.s, with his own guilt-ridden troubled P.I., Matt Scudder, itself a major contribution.

Don would laugh off the suggestion that there’s anything realistic about these novels. He would probably say that he writes melodrama (he once told me the Parker novels were “romances”…not in the Harlequin sense, of course…but I thought about that for a long time before I understood what he meant, and came to agree with it). He stopped writing Tucker Coe when, following his instincts as a real writer, he began to allow his Tobin character to grow and change and work his way out of feeling guilt. And once the character was approaching redemption, Don said, “To hell with this guy.” He told me in a letter, “He just wasn’t interesting to me any more.”

When I discovered the Westlake/Stark/Coe connection, I began collecting earlier Westlake novels and discovered that, prior to his comic side taking over the Westlake byline (and persona), Donald E. Westlake had written a handful of hard-edged hardboiled novels, and as a young man had been heralded as another Hammett. One of these books is a fine P.I. novel, KILLING TIME, which was an unusual early ’60s take on RED HARVEST, and typically uncompromising and unsentimental. There have been P.I.s in other Westlake novels and short stories, and a pseudonymous series about a TV actor turned private eye. And it should be mentioned that Stark’s Parker on occasion behaves like a private eye — much in the manner his creator writes about private eyes…reluctantly.

But Don Westlake’s right to this life achievement award really rests on two things — most obviously, the fine, short-lived but incredibly influential Mitch Tobin series, which were brought back into print not long ago. The other thing that we never acknowledge in this organization is that a writer — whose work in the crime/mystery field is not strictly P.I. — can nonetheless have a huge impact on us. The number of P.I. writers who have been influenced by both Westlake and Stark — and I proudly put myself toward the front of that line — would probably fill the room this is being read in…probably DOES fill that room.

I wish Don were here to hear me say these words. Hell, I wish I was here to hear me say these words! But we are both too busy making deadlines. (Some writers, Mr. Randisi, don’t just sit around and loaf, you know.) I am proud to be chosen to present this award to Donald E. Westlake, who was the last mystery writer I discovered as a young man — the one whose work, whose spellbinding storytelling skills and whose Swiss watchmaker’s sense of craft, taught me enough to finally make me publishable.

Sure, I stole from Westlake and Stark. If they didn’t want me to, they shouldn’t have written about thieves!

Thank you, Don. Thank you, Dick. Mr. Westlake, Mr. Stark — you’re both great P.I. writers, whether you like it or not.

Don’s Acceptance Speech read by Bob Randisi

When Bob Randisi initially told me I was going to be given this organization’s Shamus Award, my first reaction was surprise, my second was gratitude, and my third was, why me? I don’t write about private eyes.

But then I reflected further, and I remembered that in fact there have been private eyes of various sorts in my stories. Usually, they’re about twenty feet behind my guy, running hard and shouting, “Stop that man!”

Still, there they are. I think of Jacques Perly, Hammond Cash, Joe Mulligan, Ken Warren (borrowed from Joe Gores), Amos Klee, James Lawson, Fred Hoffman and, next month, Bart Hosfeld.

And even farther back, come to think of it, in my earliest days as a penman,I did tread the night-time streets disguised as a crime-fighting writer named Tucker Coe, who chronicled the doings of ex-cop sorta private eye Mitch Tobin, but soon enough he left me. He may have thought I was insincere. And even farther back, my second published Westlake novel introduced a smalltown private eye named Tim Smith, who didn’t survive the introduction. But he was there, so I thought maybe I could be legitimately among you after all.

Then I thought even more deeply on the subject, and it occurred to me that the private eye is someone who solves a problem connected with a crime, and of course that is also what my people do. They solve problems connected with a crime.

So, on behalf of those crime solvers, I do thank you for this honor, which I am irritated that I cannot accept in person. We may solve crimes, you and I, but we will never solve airlines.

That apart, I wish to thank you, sincerely and gratefully, both for myself and my guys, who would prefer — you understand — to remain anonymous.

All in all, if I don’t want to have to get a larger belt for my ego, I think it’s just as well I wasn’t there.